Remember how last week, I said that our heroes had gotten themselves into quite a pickle? Double that for this week. Now the only way to save Ariadne from a certain and excruciating death is to sacrifice Medusa instead, and oh yeah, Pasiphaê took over Atlantis while we weren't looking. I do not like this. I do not like this one bit.

Cassandra, the new Oracle, is passionately praying. She's calling to the Gods. Literally everyone who hears her pray--Pasiphaê, Melas, Medea, Ariadne, and Delmos most of all--is anxious of what she's perceiving. The Gods are angry. fucking angry. Not just a little bit angry, but 'we will fuck up your city'-angry, because 'the rightful heir of Atlantis is not recognised'. Pasiphaê is not at all happy to hear that, but even though she is scared, she still has Cassandra taken away and tries to discredit her vision. This will not end well, I promise you that.

Once in private, Pasiphaê freaks out. Medea tries to calm her, but Pasiphaê knows that when word of the Oracle's vision gets out, the people of Atlantis will turn against her. Thankfully, Cilix has an even more devious mind than her, and he spins the story: the Gods did not tell Cassandra who, exactly, the rightful heir is, so it could be Pasiphaê since she has not officially been crowned queen. It could work, Pasiphaê realizes, especially if the bribed priests tell the world all is well in the world.

Wasting no time, Pasiphaê goes to work in manipulating Ariadne to step down and make Pasiphaê queen in return for her life. She refuses, and Pasiphaê takes Delmos to torture until she can.

At the temporary oikos in the woods, Jason wants to go back to free Ariadne and fight for Atlantis. Pythagoras wisely says they can't. With Pasiphaê back, there is no way they will even be able to get into the palace, let alone to Ariadne. Jason is not happy. Someone else who is not happy is Medusa. She's sitting out in the sun, enjoying the sounds of the birds best she can. Pythagoras comes to find her. He shares his blanket (and a hug) with her. She tells him she's cursed, that she hurts everyone in her life. She'd just... damned. And she doesn't want Hercules to suffer because of her.

Ariadne's getting an update from (who I think to be) Nestor (Sam Swainsbury): Pasiphaê is killing everyone who opposes her, he doesn't have news on Delmos, nor Jason. She forces him to look for Jason outside of the city and the poor boy--because he's no more than a boy--doesn't really have a choice than to go into the mountains to the hunting lodge where Jason once took her to meet her brother.

At said lodge, Jason is experiencing epic amounts of manpain and even Hercules, King of Manpain, is done with it. He gets him some food, tries to cheer him up, taunts him, teases him, and tries to get him to react in every way possible. But, of course, it doesn't work. Jason haz a sad, and it can't be taken away with kind words, taunts, or food. Then Hercules brings up how Jason told him to keep faith and to keep fighting for Medusa and look now: they are together. Jason will have to do the same for Ariadne. It restores a little but of his old spirit.

Nestor has made it to the cabin! Hurray! He tells Pythagoras that Ariadne is still alive and that she needs them. He tells them everything that has been going on, and it's not pretty. Pythagoras sends him back to Ariadne to protect her and they will tell Jason. Medusa tells Pythagoras as soon as he is gone that they can't tell Jason. He'll just run into the fray like a lunatic and get himself killed. She has a plan to get Ariadne out of the city, but he can't tell the others. Medusa tells him to trust her.

They announce the plan (well, whatever part of it Medusa feels comfortable of sharing): Pythagoras is going back to the city. He's the only one they won't execute on the spot and he has friends who can help him. This way, they can get an update on the situation. The boys take some convincing, but they agree eventually.

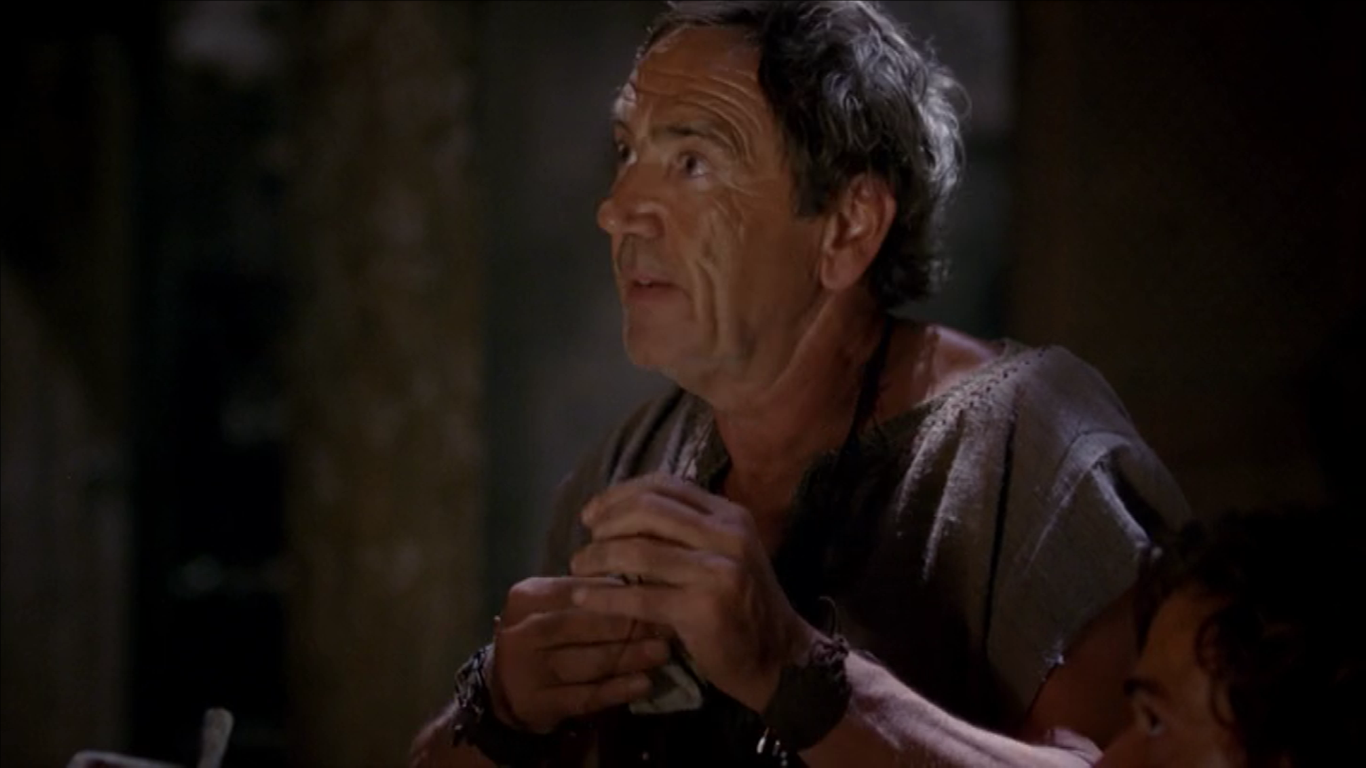

Meanwhile Melas visits Cassandra in the dungeons. She's cold and shit scared. She clings to him in desperation. Melas tells her that he knows her gift came with the condition she always tell the truth, but that she has to learn how to deliver that message carefully. In other words, to lie in order to safe her life. He hates to do it, and she hates hearing it even more. But she knows that he is only doing the things he's doing to keep her safe. the Gods will punish those who deserve punishment--he taught her that, and he mustn't forget that now.

Pythagoras packs up and leaves. Jason tells him to get word to Ariadne, Hercules to get himself wine and pie. Medusa just tells him to be strong and stay safe. He leaves.

Returning to their cell is Delmos, who has been brutally tortured. He's bloody and broken, and yet the first thing he says is that she must never, ever, give in to Pasiphaê's wishes, no matter what they do to him. She promises him, but when he turns his head away, she cries bitter tears out of guilt.

Pythagoras has reached the city and has snuck back in. It's not the city he knows though: there are bodies hanging in the street and the only people out are guards on patrol. He's not heading home, he's heading to the inventor Daidalos. Ikaros is also there, and neither of them enjoys Pasiphaê rule very much. the plan, by the way, is to retrieve Pandora's Box from the temple of Poseidon. Daidalos is in, instantly.

Ikarus goes to scout and finds out there is a group of lepers scheduled to seek Poseidon's aid. He thinks that Daidalos and Pythagoras will be cursed alongside them if they hide amongst them, but Daidalos thinks that's just superstition and refuses to entertain the thought. Meanwhile, Daidalos is making gunpowder bombs.

That night, Pythagoras and Daidalos join the lepers and enter the temple. the guards check a few of the leper to see if they are actually afflicted, but before the guards can get to them, Daidalos tosses his bomb into a fire and BOOM! No one gets seriously hurt, and no one spots Pythagoras as he sneaks into the temple to retrieve the box. Well--no one but Melas, who spots him on the way out. He wants to call the guards, but Pythagoras reminds him that this is basically all his fault and Melas guides him out of the temple by a safer route. Meanwhile Pasiphaê orders the perpetrators found and hung in the streets for all to see.

Delmos is pretty much at the end of his rope. Ariadne tries to keep him alive with words alone, but he's not doing well. He tells her he believes in her and trusts in all she will accomplish in the future. His words give her the strength she needs to turn Pasiphaê's offer down once more, even when she promises her a physician to tend to Delmos' injuries. She stands strong, she defies Pasiphaê. When Pasiphaê takes a sword and treathens to kill Delmos, she has a harder time, but he nods to tell her it's okay and she stands strong. Pasiphaê kills Delmos and tells her that if Ariadne defies her again, she will be begging for sucha swift death. She leaves Delmos' corpse in Ariadne's cell.

Pythagoras, meanwhile, has gotten out of the temple with Melas' help and out of the city with Ikaros'. He journeys back to the cabin with Pandora's box in his backpack and a heavy heart in his chest. He delivers the box to Medusa, who is waiting anxiously. He tells her she does not have to go throguh with this, but she reminds him that she is cursed and to not tell Hercules about any of this. Or Jason. In the hunting lodge, Pythagoras tells them of the state of affairs in Atlantis, and as expected, Jason immediately grabs his sword to charge the windmill. Pythagoras cools him down, but just barely.

Back in prison, Ariadne has been hung from the ceiling and she's livid. When Pasiphaê comes to once more threaten her into giving up the throne, she just snarls. That is until Pasiphaê introduced Medea, whose special brand of magic is apparently very well suited for interrogation. Pasiphaê leaves the two alone to get to work.

At the lodge, Medusa shares what she knows to be her last meal with Hercules. She tells him she loves him with such intensity that she almost gives herself away, but she manages to cover it up well enough for Hercules buys it. Pythagoras has spiked the food: he falls asleep after a few bites and she holds him tightly for long seconds before slipping from their bed and involving Jason in their plan: she wants to get back to rocking her snakes so they can use her as a weapon I do wonder why the snakes would suddenly work on Pasiphaê and Medea now, while they so clearly did not before but ey, details, right?

Jason won't have it. He says it's madness. She tells him she cannot live with what she's done. She killed the Oracle, and her curse for that is not physical, but that the guilt is killing her. This way, her death can do some good: she wants to turn back into the Gorgon, and then she wants Jason to chop off her head. Her body will only slow them down, and her head will continue to turn people to stone after her death. She rushes out in tears, and tells him to come to a nearby cave soon, because he is the only one immune. Jason rushes to wake Hercules, but Pythagoras stops him: it's the only way to save Atlantis--and by extension, Ariadne. In the cave, Medusa gathers her strength and opens the box.

Medea has done her work well. Ariadne is a ragdoll, lolling in Pasiphaê's arms when she turns her over on the ground. She whimpers and shudders. But when she blinks her eyes open, she tells Pasiphaê that there is only one true queen of Atlantis, and that it is not Pasiphaê. That's my girl! Pasiphaê says it's okay, that they will go another round tomorrow. It's only a matter of time now.

Jason comes to the cave, and the sound of serpents greets him. Medusa waits for him. She's so happy he came. She begs him to do this for her, for all of them, and while Jason cries bitter tears, he beheads her...

Hercules wakes up and finds Pythagoras waiting for him. Pythagoras tells him of the decision medusa made and he is... beyond anger, beyond sadness. He throws Pythagoras around the cabin and then sags into a heap to cry like no man should ever have to cry in their lives--like no person should. Meanwhile Jason returns to Atlantis and turns an entire squadron of guards to stone.

Goran rushes to Pasiphaê to tell her about the one man army with the Gorgon's head and she panics. She tells him to keep the men away, takes his sword, and waits for Jason to come to her. Because he will. She knows he will. They play a game of cat and mouse in the palace halls and eventually, they stumble upon each other. She is still not affected by the snakes, but he doesn't need them to: he has his sword, and he will kill her. The struggle is very quick: Pasiphaêis not a trained fighter, and he is. She tells him why he won't kill her: because she's his mother. He's shocked, amazed, and indeed removes his sword from her neck. Then he knocks her unconscious with the pummel of the sword. He tries to kill her again, but he can't. He tosses his sword and Medea shows up. She tells him it's true, that Pasiphaê is his mother. That he is touched by the Gods. That this is why he can look upon the Gorgon without turning to stone. That is when she drops the other bomb: they feel this way about each other because they are both touched by the Gods. He snarls that he doesn't feel anything for her.

Jason rushes to free Ariadne and he hands her a blindfold. She ties it around her head instantly and takes his arm. With the Gorgon's head in hand, he guides her out of the dungeons, out of the palace, and out of Atlantis.

Next time on Atlantis: Jason is feeling the weight of his heritage, daddy dearest returns, and Jason and Medea kiss. Saturday on BBC One, recap on Monday.