Perseus is one of ancient Hellas' greatest heroes, and it is not odd that he was immortalized in the night's sky. He is--of course--linked to the many

constellations dedicated to the rescue of Androméda, but there is far more tot he hero Perseus.

Perseus was born to Danae, who was locked in a bronze chamber by her father Akrisios, where she was impregnated by Zeus in the form of a golden shower. Akrisios put both mother and child in a chest and set them adrift on the sea, but they washed safely ashore on the island of Seriphos. From Hyginus' '

Fabulae':

"Danaë was the daughter of Acrisius and Aganippe. A prophecy about her said that the child she bore would kill Acrisius, and Acrisius, fearing this, shut her in a stone-walled prison. But Jove, changing into a shower of gold, lay with Danaë, and from this embrace Perseus was born. Because of her sin her father shut her up in a chest with Perseus and cast it into the sea. By Jove’s will it was borne to the island of Seriphus, and when the fisherman Dictys found it and broke it open, he discovered the mother and child. He took them to King Polydectes, who married Danaë and brought up Perseus in the temple of Minerva. When Acrisius discovered they were staying at Polydectes’ court, he started out to get them, but at his arrival Polydectes interceded for them, and Perseus swore an oath to his grandfather that he would never kill him. When Acrisius was detained there by a storm, Polydectes died, and at his funeral games the wind blew a discus from Perseus’ hand at Acrisius’ head which killed him. Thus what he did not do of his own will was accomplished by the gods. When Polydectes was buried, Perseus set out for Argos and took possession of his grandfather’s kingdom." [63]

The story of Perseus is somewhat chaotic; his myths have been told and retold many times--even in ancient times--and what happens to Perseus next is most certainly up for debate. To quote the 'Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology':

"According to a later or Italian tradition, the chest was carried to the coast of Italy, where king Pilumnus married Danaë, and founded Ardea (Virg. Aen. vii. 410; Serv. ad Aen. vii. 372); or Danaë is said to have come to Italy with two sons, Argus and Argeus, whom she had by Phineus, and took up her abode on the spot where Rome was afterwards built (Serv. ad Aen. viii. 345). But, according to the common story, Polydectes, king of Seriphos, made Danae his slave, and courted her favour, but in vain. Another account again states that Polydectes married Danae, and caused Perseus to be brought up in the temple of Athena. When Acrisius learnt this, he went to Polydectes, who, however, interfered on behalf of the boy, and the latter promised not to kill his grandfather. Acrisius. however, was detained in Seriphos by storms, and during that time Polydectes died. During the funeral gaines the wind carried a disk thrown by Perseus against the head of Acrisius, and killed him, whereupon Perseus proceeded to Argos and took possessions of the kingdom of his grandfather (Hygin. Fab. 63)."

No matter the version of the tale, Perseus' greatest heroic deed is what follows: the hunt for

Médousa. In the most common versions of the story, Polydektes did not yet marry Danae, but wished to. A now grown up Perseus did not trust Polydektes and tried to keep him away from his mother, so Polydektes had to come up with a plan. He said he would marry Hippodameia--tamer of horses--and asked Perseus for a horse to give as a wedding present. Perseus didn't have one to give, so he told Polydektes to name any other favour, and that he would not refuse. Polydektes then instructed him to cut off and bring back the head of a Gorgon, and Perseus was trapped. From Apollodorus' '

Bibliotheca' we learn the following:

"So with Hermes and Athene as his guides Perseus sought out the Phorkides (daughters of Phorkys), who were named Enyo, Pephredo, and Deino. The three of them possessed only one eye and one tooth among them, which they took turns using. Perseus appropriated these and when they demanded them back, he said he would return them after they had directed him to the Nymphai. These Nymphai had in their possession winged sandals and the kibisis, which they say was a knapsack. (Pindaros and Hesiodos in the Shield of Herakles, describe Perseus as follows : `The head of a terrible monster, Gorgo, covered all his back, and a kibisis held it.’ It is called a kibisis because clothing and food are placed in it.). They also had the helmet of Haides. When the Phorkides had led Perseus to the Nymphai, he returned them their tooth and eye. Approaching the Nymphai he received what he had come for, and he flung on the kibisis, tied the sandals on his ankles, and placed the helmet on his head. With the helmet on he could see whomever he cared to look at, but was invisible to others.

Perseus took flight and made his way to the Okeanos, where he found the Gorgones sleeping. Their names were Stheno, Euryale, and the third was Medousa, the only mortal one : thus it was her head that Perseus was sent to bring back. The Gorgones’ heads were entwined with the horny scales of serpents, and they had big tusks like hogs, bronze hands, and wings of gold on which they flew. All who looked at them were turned to stone. Perseus, therefore, with Athena guiding his hand, kept his eyes on the reflection in a bronze shield as he stood over the sleeping Gorgones, and when he saw the image of Medousa, he beheaded her. (As soon as her head was severed there leaped from her body the winged horse Pegasos and Khrysaor, the father of Geryon. The father of these two was Poseidon.) Perseus then placed the head in the kibisis and headed back again, as the Gorgones pursued him through the air. But the helmet kept him hidden, and made it impossible for them to identify him.” [2. 36 - 42]

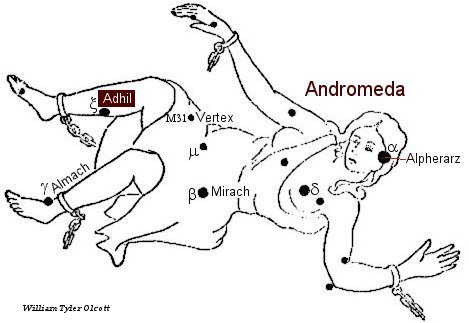

With Médousa's head secured, Perseus headed back to Polydektes, but was stopped while on route by the vision of a woman, chained to a rock, about to be devoured by a sea monster. It had been a dark day for

Cepheus, king of Aethiopia, when he had heard his wife

Cassiopeia boast that her daughter

Androméda was more beautiful than the Nereids. Shocked, he had tried to silence his wife, but it was too late. The father of the Nereids, the sea God Nereus, had heard Cassiopeia's prideful boast and had brought his grievance to Poseidon. Poseidon had ruled in favour of Nereus and sent

Cetus, a huge sea monster, to ravage the coasts of Aethiopia. Nereus would only be appeased when Cepheus sacrificed his daughter to Cetus. Cepheus had refused, but when the terror continued, Androméda had offered herself up to be sacrificed. Fast forward to Andromeda, chained to the rocks, about to die. Perseus pulled Médousa's head out of his bag and petrified Cetus with it before undoing Androméda's bindings. He fell for the beautiful princess instantly, and desired to take her as his wife. In most versions of the myth, he is allowed, but Hyginus in his '

Fabulae' has a different story to tell:

"When he wanted to marry her, Cepheus, her father, along with Agenor, her betrothed, planned to kill him. Perseus, discovering the plot, showed them the head of the Gorgon, and all were changed from human form into stone. Perseus with Andromeda returned to his country." [64]

Perseus eventually married Androméda and took her off to his native island of Serifos. They had many children; sons Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, and Electryon, as well as daughters, Autochthe and Gorgophone. According to Hyginus in his 'Astronomica', Perseus was committed to the stars for the following reasons:

"He is said to have come to the stars because of his nobility and the unusual nature of his conception."

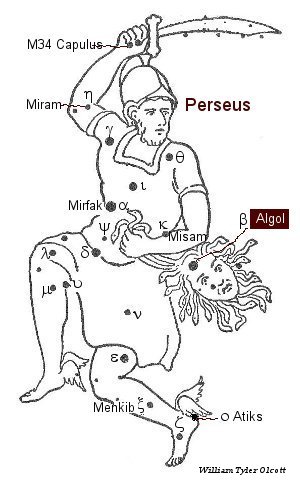

The constellation Perseus is visible at latitudes between +90° and −35° and best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of December.