The Minister of Culture Lina Mendoni vowed to restore the ancient burial site of Doxipara located in Evros in northeast Greece which she described as having an “indisputable archaeological and historical value.”

During her recent visit to the site, Mendoni said that a museum will be build to showcase the tomb which dates back to the 2nd century AD. Archaeologists say that four members of a rich family who died successively, were cremated and buried at the site, and the large burial tumulus of Doxipara was built in memory of them.

The excavations of the burial tumulus of Doxipara began in 2002 and brought to light four cremation pits, which contained residue of incineration from what is believed to be two middle-aged men, a young man, and a young woman.

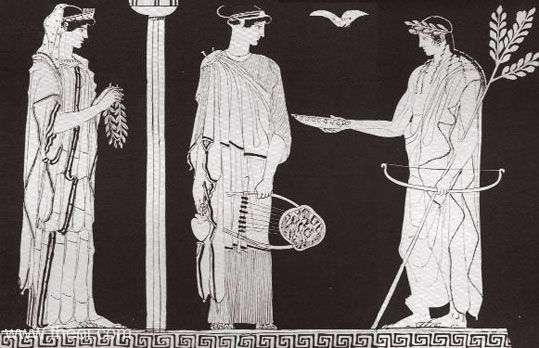

In these pits of the burial tumulus of Doxipara a number of objects were also discovered that accompanied the dead to the other world, according to the traditions of that time; clay and bronze pottery, lamps, and lanterns, weapons and jewelry were among the findings.

What makes the Burial Tumulus of Doxipara important is the discovery of five carriages, buried together with their five horses around the tumulus. Such findings have been found in Asia and Europe, but this the first discovery specifically in Greece. Four-wheel carriages were used for the transport of the dead to incineration and burial.

During her recent visit to the site, Mendoni said that a museum will be build to showcase the tomb which dates back to the 2nd century AD. Archaeologists say that four members of a rich family who died successively, were cremated and buried at the site, and the large burial tumulus of Doxipara was built in memory of them.

The excavations of the burial tumulus of Doxipara began in 2002 and brought to light four cremation pits, which contained residue of incineration from what is believed to be two middle-aged men, a young man, and a young woman.

In these pits of the burial tumulus of Doxipara a number of objects were also discovered that accompanied the dead to the other world, according to the traditions of that time; clay and bronze pottery, lamps, and lanterns, weapons and jewelry were among the findings.

What makes the Burial Tumulus of Doxipara important is the discovery of five carriages, buried together with their five horses around the tumulus. Such findings have been found in Asia and Europe, but this the first discovery specifically in Greece. Four-wheel carriages were used for the transport of the dead to incineration and burial.