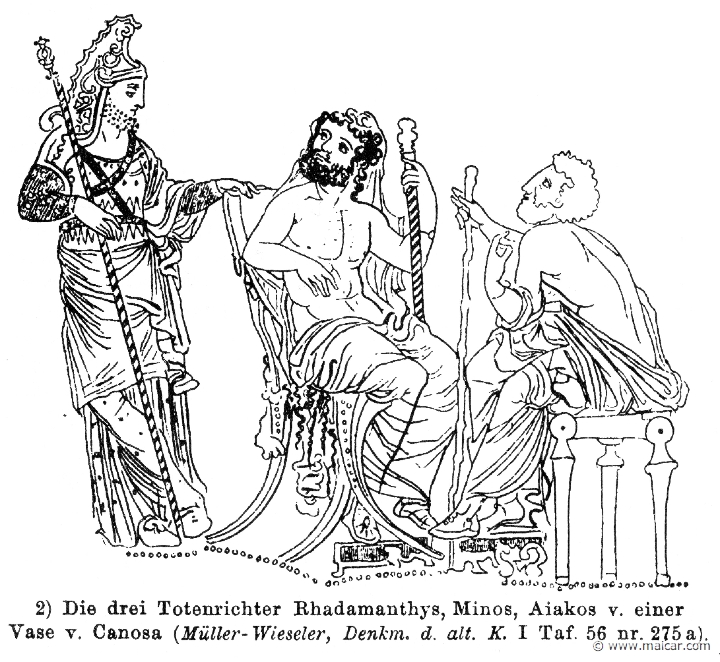

At the end of last year, I wrote a long and detailed post about the Hellenic Underworld. In it, I mentioned the judges of the dead: Minos, Rhadamanthys and Aiakos. All three of the judges were human once, and all three were selected for certain unique qualities. As these three are some of the most powerful demi-Gods who will ever touch our lives, I want to discuss them further today.

Thanks to the ancient writers, we know quite well who the judges are and why they were appointed to the position. From Plato's Gorgias comes this long but very clear description:

And so we have three judges, Rhadamanthys for those from Asia Minor, Aiakos for those from Europe, and Minos to make the final decision. And so the question remains, who are these three, and why were they worthy enough to become a judge of the dead?

Minos (Μίνως) was a king of Krete, son of Zeus and Europa. He is most famous for the labyrinth of the Minotaur under his fantastic palace where Daidalos and Íkaros were kept until their escape. He died in pursued of them, killed while taking a bath--either by Daidalos, or by the daughters of King Kokalus with whom Minos was staying. How can a man as cruel as Minos become a fair judge of the dead? Plutarch, in Perseus, says the following about it:

Rhadamanthys (Ραδαμανθυς) was Minos' brother in most versions of mythology, although he could also have been the son of Hēphaistos. During his life, he was a lawmaker, judge and ruler in the court of Minos. In some versions of the myth, he was Ariadne's husband, instead of Dionysos. It seems Minos may have been jealous of Rhadamanthys' popularity, and Rhadamanthys was forced to flee the island of Krete. During his exile, he met and married Alkmene, mother of Hēraklēs, who had been left without a husband after Amhitryon passed. After his death, he went to Elysium, and became a judge, as a reward for living a just and lawful life. From Pindar's Olympian Ode comes the following praise:

Aiakos (Αἰακός) was the son of Zeus and Aegina, a daughter of the river-god Asopus. He was born on the island of Oenopia--later renamed Aegina--to which Aegina had been carried by Zeus to secure her from the anger of her parents. Aiakos is also sometimes mentioned as a son of Europa. While he reigned in Aegina, he was renowned in all of Hellas for his justice and piety, and was frequently called upon to settle disputes not only among men, but even among the gods themselves. After his death, Aiakos became one of the three judges in Hades, and according to Plato especially for the shades of Europeans. Apollodorus in his Bibliotheca describes Aiakos:

And so, these are the three judges who rule over us in death. Let me end this with a little Hellenic advice, noted down by Seneca, Roman Stoic philosopher and playwright, from his tragedy 'Hercules Furens':

Thanks to the ancient writers, we know quite well who the judges are and why they were appointed to the position. From Plato's Gorgias comes this long but very clear description:

"Now in the time of Kronos there was a law concerning mankind, and it holds to this very day amongst the gods, that every man who has passed a just and holy life departs after his decease to the Isles of the Blest, and dwells in all happiness apart from ill; but whoever has lived unjustly and impiously goes to the dungeon of requital and penance which, you know, they call Tartaros. Of these men there were judges in Kronos' time, and still of late in the reign of Zeus--living men to judge the living upon the day when each was to breathe his last; and thus the cases were being decided amiss.

So Plouton [Haides] and the overseers from the Isles of the Blest came before Zeus with the report that they found men passing over to either abode undeserving.

Then spake Zeus: 'Nay,' said he, 'I will put a stop to these proceedings. The cases are now indeed judged ill and it is because they who are on trial are tried in their clothing, for they are tried alive. Now many,' said he, `who have wicked souls are clad in fair bodies and ancestry and wealth, and at their judgment appear many witnesses to testify that their lives have been just. Now, the judges are confounded not only by their evidence but at the same time by being clothed themselves while they sit in judgment, having their own soul muffled in the veil of eyes and ears and the whole body. Thus all these are a hindrance to them, their own habiliments no less than those of the judged.

Well, first of all,' he said, 'we must put a stop to their foreknowledge of their death; for this they at present foreknow. However, Prometheus has already been given the word to stop this in them. Next they must be stripped bare of all those things before they are tried; for they must stand their trial dead. Their judge also must be naked, dead, beholding with very soul the very soul of each immediately upon his death, bereft of all his kin and having left behind on earth all that fine array, to the end that the judgment may be just.

Now I, knowing all this before you, have appointed sons of my own to be judges; two from Asia, Minos and Rhadamanthus, and one from Europe, Aiakos. These, when their life is ended, shall give judgment in the meadow at the dividing of the road, whence are the two ways leading, one to the Isles of the Blest, and the other to Tartaros. And those who come from Asia shall Rhadamanthys try, and those from Europe, Aiakos; and to Minos I will give the privilege of the final decision, if the other two be in any doubt; that the judgment upon this journey of mankind may be supremely just."

And so we have three judges, Rhadamanthys for those from Asia Minor, Aiakos for those from Europe, and Minos to make the final decision. And so the question remains, who are these three, and why were they worthy enough to become a judge of the dead?

Minos (Μίνως) was a king of Krete, son of Zeus and Europa. He is most famous for the labyrinth of the Minotaur under his fantastic palace where Daidalos and Íkaros were kept until their escape. He died in pursued of them, killed while taking a bath--either by Daidalos, or by the daughters of King Kokalus with whom Minos was staying. How can a man as cruel as Minos become a fair judge of the dead? Plutarch, in Perseus, says the following about it:

"Hesiod called him [Minos] 'most royal,' or that Homer styled him 'a confidant of Zeus,' but the tragic poets prevailed, and from platform and stage showered obloquy down upon him, as a man of cruelty and violence. And yet they say that Minos was a king and lawgiver, and that Rhadamanthys was a judge under him, and a guardian of the principles of justice defined by him."

Rhadamanthys (Ραδαμανθυς) was Minos' brother in most versions of mythology, although he could also have been the son of Hēphaistos. During his life, he was a lawmaker, judge and ruler in the court of Minos. In some versions of the myth, he was Ariadne's husband, instead of Dionysos. It seems Minos may have been jealous of Rhadamanthys' popularity, and Rhadamanthys was forced to flee the island of Krete. During his exile, he met and married Alkmene, mother of Hēraklēs, who had been left without a husband after Amhitryon passed. After his death, he went to Elysium, and became a judge, as a reward for living a just and lawful life. From Pindar's Olympian Ode comes the following praise:

"Those [of the dead] who had good courage, three times on either side of death, to keep their hearts untarnished of all wrong, these travel along the road of Zeus to Kronos’ tower. There round the Islands of the Blest, the winds of Okeanos play, and golden blossoms burn, some nursed upon the waters, others on land on glorious trees; and woven on their hands are wreaths enchained and flowering crowns, under the just decrees of Rhadamanthys, who has his seat at the right hand of the great father [Kronos], Rhea’s husband, goddess who holds the throne highest of all." [2.63]

Aiakos (Αἰακός) was the son of Zeus and Aegina, a daughter of the river-god Asopus. He was born on the island of Oenopia--later renamed Aegina--to which Aegina had been carried by Zeus to secure her from the anger of her parents. Aiakos is also sometimes mentioned as a son of Europa. While he reigned in Aegina, he was renowned in all of Hellas for his justice and piety, and was frequently called upon to settle disputes not only among men, but even among the gods themselves. After his death, Aiakos became one of the three judges in Hades, and according to Plato especially for the shades of Europeans. Apollodorus in his Bibliotheca describes Aiakos:

"Aiakos was the most religious of all men . . . and Aiakos, even after death, is honoured in the company of Plouton [Haides], and has charge of the keys of Haides’ realm."

And so, these are the three judges who rule over us in death. Let me end this with a little Hellenic advice, noted down by Seneca, Roman Stoic philosopher and playwright, from his tragedy 'Hercules Furens':

"Is the report true that in the underworld justice, though tardy, is meted out, and that guilty souls who have forgot their crimes suffer due punishment? Who is that lord of truth, that arbiter of justice? Not one inquisitor alone sits on the high judgment-seat and allots his tardy sentences to trembling culprits. In yonder court they pass to Cretan Minos’ presence, in that to Rhadamanthus’, here [Aiakos] the father of Thetis’ spouse gives audience. What each has done, he suffers; upon its author the crime comes back, and the guilty soul is crushed by its own form of guilt. I have seen bloody chiefs immured in prison; the insolent tyrant’s back torn by plebeian hands. He who reigns mildly and, though lord of life, keeps guiltless hands, who mercifully and without bloodshed rules his realm, checking his own spirit, he shall traverse long stretches of happy life and at last gain the skies, or else in bliss reach Elysium’s joyful land and sit in judgment there. Abstain from human blood, all ye who rule: with heavier punishment your sins are judged." [2.731]

-

Friday, May 10, 2013

Aiakos Alkmene Amphitryon Daidalos death Hēraklēs Minos Mythology 101 Pagan Blog Project Rhadamanthys Seneca