A few days ago, PaganSquare blogger Gus diZerega posted a blog post on nature religions within Paganism, a reply to a lovely post by

Joseph Bloch. Paganism--as used by Gus--seems to include any pre-Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic religion, and is separate from Neo-Paganism, which he classifies as 'modern revival of Pagan spirituality by people coming from within modern society'. The focal point of Gus' post was that, whether the ancient or modern Pagan cultures agree or not, they were, and are, nature worshippers. As such, reconstructionists of said religions are also nature worshippers. I'm paraphrasing here, so please,

read Gus' words for yourself.

I disagree with Gus' conclusions, but I will not go into his writing here. I simply introduce Gus and his post to introduce PaganSquare reader Trine, who commented on one of my replies to Gus with a question I would love to dedicate a blog post to. Her post went as follows:

"I am curious - would you be interested in writing a blog post on your Hellenistic view on the reverence of (or indifference to) nature and on pollution? What I read above is that oil spills, trash in the woods, bee hive death due to insecticides, etc. does not really concern you as much as other topics may, because Hellenism is not a nature-based religion. My question, or curiosity, regards how you would approach this in terms of your Gods - is an oil spill offensive to Poseidon? Is littering in the wild and limiting the natural habitats of wildlife offensive to Pan, or Artemis? And how did the Hellenes approach this?"

The first thing I will say, is that I am not an expert on anything, and the second that other Hellenists will have different views on this subject. It all depends on where you

draw your inspiration for Reconstruction from; there are, after all, philosophical foundations for a more 'nature based Hellenismos', as we will see. What this post will focus on most, is that religion, philosophy, and ethics are connected, but they are not completely codependent. I don't want to spoil the surprise, but the conclusion of this post will be that nature is important within Hellenismos--it is partly though nature, after all, that the Theoi can manifest--but the focus in Hellenismos is different than in a nature based religions.

Perhaps I should take the time here to express my definition of 'nature worship'. Nature worship, for me, is a system of religion based on the veneration of natural forces and phenomenon--for example, celestial objects such as the sun and moon and terrestrial objects such as the elements, trees, and rain. These are seen as sacred, or holy, unto themselves, and not in relation to a deity or other higher power. In many nature religions, nature as a whole is considered a--or the--(supreme) deity, if the worship of Gods is included in the practice. Because nature and natural phenomenon are considered sacred or divine; preservation, eco-warriorship, and the minimization of the carbon footprint are often important influences within the religion or Tradition. The best description I have ever read of the practice of nature worship comes from Edain McCoy, whose teachings I have

quite a bit of trouble with, but the quote applies and goes:

"The cycles of nature are our holy days, the earth is our temple, its plants and creatures our partners and teachers."

I think this is a beautiful sentiment, and have even felt this way for a good few years when I was just starting out. I still care greatly about the environment, and I recycle, try to take public transportation, and turn off the lights when I leave the house. I don't litter, and I try to pick up other people's trash whenever I'm out for a nature walk. I will most certainly call out those I see littering. I eat organic meat--if I eat meat at all--and buy animal products which have provided the best possible life to the animal the product came from. All of that, however, is not directly tied to my religion. It's because I'm a decent human being, who is aware of the destructive influence of humanity on the natural world, and if I have kids some day, I would like to leave them some of the beauty that the natural world can offer.

As for Hellenismos; Hellenismos has two major focus points: the Theoi, and community. Both are connected in some way to nature--both in a negative, and a positive way--but are also distinctly separate from it. The Theoi make Their presence known to us through natural phenomenon. Zeus Ombrios, for example, controls rain and thunderstorms. We might see a fight between Gods and giants in the

eruption of a volcano. As ancient Hellenic philosopher Thales of Milete said: "all things are full of Gods".

Community mattered greatly, because the influence of one, could impact the many. If one person upset the Gods, the entire village of city could be punished--as the other members of the community did not stop this

hubris. It was largely because of this dynamic,

Socrates was put to death. In another

response to a reader question, I discussed that everyone who was allowed to attend public festivals--and that differed per festival--was present for them, as it was a massive, state funded, boost of

kharis for the city-state as well as everyone who attended.

When the Gods are displeased with us, They might fail the harvest, flood our lands, wreak havoc with earthquakes, or punish us in any number of other--nature related--ways. As such, proper worship of the Theoi was important. A natural disaster would always be followed by a flurry of divination and sacrifice: in order to prevent a second--perhaps even worse--disaster, it was vital to discover which Theos or Theia was displeased, and to appease Them with ritual and sacrifice. Perhaps, then, the Gods would look favorably upon Their followers again. Besides shared worship, the focus on community allowed the ancient Hellenes to survive, despite the hardship that the natural world could bestow upon them.

The ancient Hellenes lived in and with nature, but also struggled against it. Because the world was a dangerous place, it was vitally important to appease the Theoi closely connected to (natural) phenomenon before stepping out into it. Because of this, sailors would offer to Poseidon, traveling merchants would sacrifice to Hermes, and farmers would offer to Demeter. They hoped that their boat would not sink, that they would not be robbed and killed, and that their crops would grow, so they would have food to eat and surplus to trade or sell.

To return to the reader question: pollution wasn't a much known thing or issue in ancient Hellas. While the ancient Hellenes did some permanent damage to the environment--most notably in the poisoning of soil and water with mercury and lead--the extent of pollution was such that nature's natural processes could balance it out pretty decently. Modern day pollution is, of course, a fair bit more severe. It is everywhere. We're draining the planet dry, cutting forests down unapologetically, littering, overfishing, etc.

It is important to note that--especially post-Plato--the world was seen as a living organism on its own, which contained all other living organisms (a precursor to Lovelock's much later 'Gaia Theory'). Plato emphasized the interdependence between the micro and the macro, nature within and without. He also introduced or popularized the notion that the world was not created by the Gods, but that the Gods are craftsmen, fashioning a pre-existing and disordered natural world to make it fit an eternal and ideal pattern. The Hellenes before Plato would not share many of these ideas, so we return to the question of inspiration: from which time period does the reconstructionist reconstruct his or her practice?

If we look at Plato and Lovelock, we might interpret recent earthquakes, tsunamis, droughts, and other natural disasters as the planet's way of protecting itself from the influence of humanity. If we take this standpoint, and look at the philosophies of the Hellenic time period before Plato, we could still interpret these natural disasters as the will of the Gods. We explain modern ecological issues--global warming, for example--in a scientific manner, but that scientific phenomenon might just as well be the hand(s) of the Gods, like the ancient Hellenes believed. The Gods, or Lovelock's Gaia, displeased with humanity's disrespect of nature, of Them, of ourselves, of each other, or for any other number of reasons. I am getting a bit off-topic here, however.

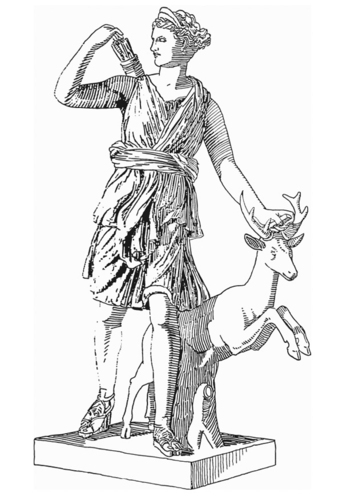

I think we need to take better care of our planet, but I think the interpretation that an oil spill offends Poseidon is a modern one. It is such by necessity--as there were no oil spills in ancient Hellas--but it is important to note that Poseidon has control of the sea, He is not the sea. He might manifest in the wave that topples the boat, but He is not the wave. This is, in my view, the major difference between the ancient religions and the modern nature religions: the ancient Gods control nature, they are not nature itself. I do not worship Demeter by farming fields of gain, but I will need Her blessing if I want my harvest to succeed. I do not commit an offense towards Artemis by cutting down a forest, but She might still punish me for my actions if She had other plans for that forest, or the animals in it.

In ancient Hellas, there were small shrines put up at certain trees, lakes, and other features of nature: these were placed there to honor the home of the

nymphs, and usually worshipped the nature spirit of said place, as well as the Theoi they were connected with. I mention the nymphs, because in the worship of dryad, nereids, oreads, and many of the others, one could potentially see the worship of nature. After all, this worship centers around a tree, a lake, a mountain, or any other feature of the landscape. Yet, the honors went to whomever lived inside that feature of the landscape, and while these beings were--and are--usually tied to this feature, they are, again, not part of it.

The ancient Hellenes were dependent on nature. There is no denying that. It is only logical that the Gods of the ancient Hellenes controlled that very nature the ancient Hellenes were so dependent on. This holds true today as well, even though the western world has largely lost sight of the role of nature in our lives. We perceive--by and large--that our food comes from the supermarket, not the field. If we need something, we order it with the click of a mouse button. If our car is out of gas, we fill up the tank at the nearest gas station.

Modern Hellenists have the religious obligation to retrace the route our household items have taken, and give proper thanks to the Theos or Theia who made it possible for us to make use of these items. The modern human has the ethical obligation to look at the way these items were produced--by the hand of child workers, sprayed with chemicals, at the expense of animals, etc--and decide if this is a trend they want to have continued. For Hellenists--who pride themselves on having a strong ethical framework--their actions might lean towards ecological activism, or at least personal 'green' behavior, but I dare say that this is philosophy, not religion, and there is

a difference between the two. Religion and philosophy have a different goal; one to guide mankind in the way of the Theoi, the other to understand mankind. Both fuel the ethical framework of a person, but only one is religion.

My religion is not a nature religion: my religion focuses on the Theoi, and the influence They have on my life, and the lives of those I love. Nature, in my religious views, is a medium through which my Gods can manifest. My philosophical views inspire me to see the world as a beautiful whole, of which I am am a tiny part. My ethical framework requires me to take responsibility for my consumption of goods and services, and to limit the harm I do to my environment to the best of my abilities. I am not an eco-warrior. That is not my ethical path in life, but I am a 'green' person. Yet, my ethical framework is not my philosophy, nor my religion. My philosophy is not my religion, nor my ethical framework, and my religion is not my ethical framework nor my philosophy. The three overlap, are tied together in a way that cannot be unbound, but they are not the same. This is why my religion is not a nature religion.