When I was still an avid D&D player, my group tended to happen or seek out an oracle or diviner quite often. In one campaign, my character famously ended up leading the entire arty to its death because he didn't understand the oracular messages he was receiving in his dreams. No one was mad, though: that character was truly the worst character I ever played to send oracular messages to.

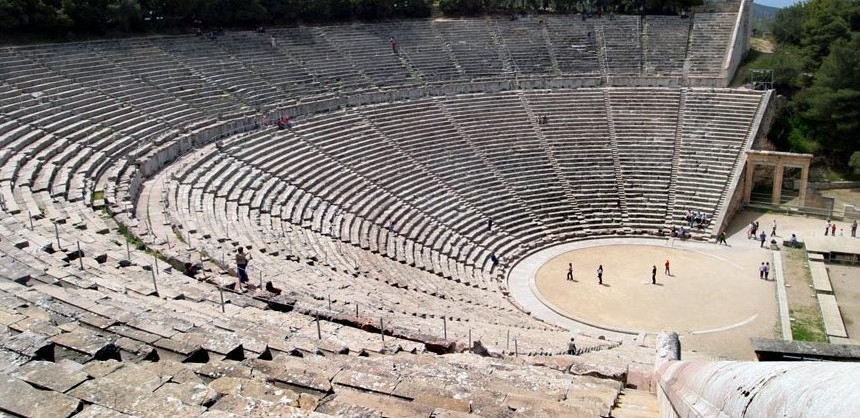

Oracles tend to be vague in some way: either you have a binary oracle, which gives you a 'yes' or 'no' answer but doesn't give you any details or nuance (i.e. "am I going to die?" "yes", but there is no way to discern when it is going to happen), or a conversational oracle like at

Delphi, which tended to give a riddle for an answer--one that could be, and often was, misinterpreted.

A beautiful example of this is King Kroisos (Κροῖσος), the king of Lydia from 560 to 547 BC, who asked Apollon at Delphi if he should continue his campaign against the Persians. Apollon answered that, if he did attacked the Persians, "he would destroy a great empire". Kroisos figured this meant he would succeed while, in the end, it was his own that was destroyed.

Us D&D players learned early on that, if we wanted an answer we could use from the oracles we procured, we needed to be crystal clear in the way we asked our question. I'm fairly certain the ancient Hellenes would have realized this too: if there is no room for ambiguity in the question, a lot of hardship can be prevented, after all. If the oracular question is: "Who will be king?", the answer can be quite vague, indeed, but if the question is 'Give us the name of the man who will rule Athens as king after the king who now sits on the throne of Attica is no longer able to", there will be a lot less room for maneuvering. So why, in general, didn't the ancient Hellenes phrase their answers differently?

I, for one, think there are at least two primary reasons: one answer is that the ancient Hellenes might simply have liked riddles and riddling situations. The sage Kleoboulos (

Κλεόβουλος) who lived around 600 BC collected more than 3,000 riddles. The most famous heroes of Hellenic myth excelled in solving riddles; Oedipus, for example, who cracked the

riddle of the Sphinx. The ancient heroes also excelled in disguising one thing as another, which requires a shrewdness one must also possess to solve a riddle. Most famously, Odysseus did this with the wooden horse at Troy, and again in the cave of the Cyclops where he hid himself away and told the Cyclops his name was 'no one', so that when the Cyclops called out for aid, he could only say that no one was hurting him--and so his fellow Cyclops' did not come to his aid.

Many--if not all--myths are layered with meaning, challenging the reader or listener to go beyond the story to find valuable lessons on life and the Theoi. it seems the ancient Hellenes had a knack for encoding and decoding meaning, and might have enjoyed this so much, they did not want to take away from their oracular messages by forcing a 'yes' or 'no' answer.

A second answer may be that the ancient Hellenes considered riddles as oracular messages acceptable might be destiny. What shall come to pass, will come to pass if the Theoi so desire. The oracular message and the interpretation of the subject and those around him have a part to play in how events are about to unfold. If the subject is destined to 'change his destiny', he will understand the hidden meaning and act accordingly; if he isn't, he will fail to see beyond the hidden meaning and the events will come to pass, regardless. One of the best examples of this is Aegeus, who visited the oracle of Delphi to get an answer on how to beget a son. in the famous words of Apollodorus in his '

Library':

"After the death of Pandion his sons marched against Athens, expelled the Metionids, and divided the government in four; but Aegeus had the whole power. The first wife whom he married was Meta, daughter of Hoples, and the second was Chalciope, daughter of Rhexenor. As no child was born to him, he feared his brothers, and went to Pythia and consulted the oracle concerning the begetting of children. The god answered him:

'The bulging mouth of the wineskin, O best of men, loose not until thou hast reached the height of Athens.'

Not knowing what to make of the oracle, he set out on his return to Athens. And journeying by way of Troezen, he lodged with Pittheus, son of Pelops, who, understanding the oracle, made him drunk and caused him to lie with his daughter Aethra. But in the same night Poseidon also had connection with her. Now Aegeus charged Aethra that, if she gave birth to a male child, she should rear it, without telling whose it was; and he left a sword and sandals under a certain rock, saying that when the boy could roll away the rock and take them up, she was then to send him away with them."

For those who have no idea of the identity of the child: the child was the great hero

Theseus, and the Gods seem to have decreed that Theseus should be born by Aethra, not Chalciope, and those who understood--and did not understand--the oracular message did so for a reason.

Riddles were and are important tools, and they make divination such a difficult--and dangerous--thing to do. When I track the movement of birds, or when I lay down tarot cards, I know that I am perceiving a riddle, not an answer. The answer is in there, somewhere, but never be fooled into thinking that what you see is all there is to see: it might be all you were meant to see, however.