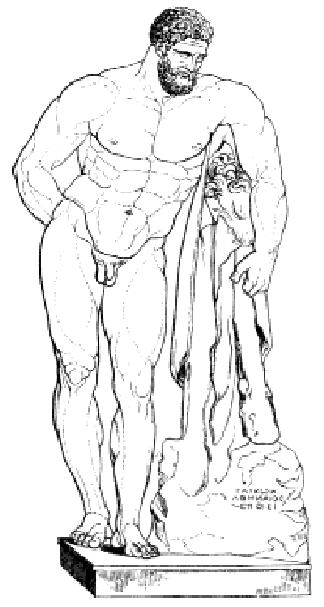

It's been a while since we last journeyed with Hēraklēs. In fact, the last time we did, he had just completed the tenth labour: obtain the cattle of the monster Geryon. Geryon (Γηρυών) was the son of Khrysaor and Kallirrhoe and grandson of Medusa,

was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides

in the far west of the Mediterranean. Hēraklēs did away with him easily, even though getting to him proved to be quite the journey.

Now, the original mission in order to be cleansed of the act of killing his own children in a rage brought on by Hera was to perform ten heroic labours in ten years for the king of Tiryns, Eurystheus. But Eurystheus discounted two of the labours, labour two: slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra, and labour five: clean the Augean stables in a single day because he felt Hēraklēs had cheated on both. Now it is up to Hēraklēs to perform an eleventh labour: to steal the apples of the Hesperides (Ἑσπεριδες).

The Hesperides are nymphs, Goddesses of the evening and golden light of sunset. The three nymphs were daughters of either Nyx or the heaven-bearing Titan Atlas. They were entrusted with the care of the tree of the golden apples which was first presented to the Goddess Hera by Gaia on her wedding day. They were assisted in their task by a hundred-headed guardian drakon named Ladon (Λαδων). As Appolodoros writes in his 'Library':

Of course, nothing is ever easy for our hero. Getting to the apples is harder than getting them! Before he could even get to work, Hēraklēs met Cycnus, a fellow hero, son of Ares . Zeus stopped the battle before it could get out of hand. Traveling on, Hēraklēsfought the sea God Nereus for the location of the garden where the tree of the golden apples stood. He wrestled the location out of the Gods and travelled to Lybia where he was challenged by Antaeus, son of Poseidon, who had the habit of challenging and killing strangers, only Hēraklēs killed him instead. Afterwards, Apollodorus tells us:

According to Hyginus, Ladôn was put into the sky as the constellation Draco.

Now, the original mission in order to be cleansed of the act of killing his own children in a rage brought on by Hera was to perform ten heroic labours in ten years for the king of Tiryns, Eurystheus. But Eurystheus discounted two of the labours, labour two: slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra, and labour five: clean the Augean stables in a single day because he felt Hēraklēs had cheated on both. Now it is up to Hēraklēs to perform an eleventh labour: to steal the apples of the Hesperides (Ἑσπεριδες).

The Hesperides are nymphs, Goddesses of the evening and golden light of sunset. The three nymphs were daughters of either Nyx or the heaven-bearing Titan Atlas. They were entrusted with the care of the tree of the golden apples which was first presented to the Goddess Hera by Gaia on her wedding day. They were assisted in their task by a hundred-headed guardian drakon named Ladon (Λαδων). As Appolodoros writes in his 'Library':

"When the labours had been performed in eight years and a month, Eurystheus ordered Hercules, as an eleventh labour, to fetch golden apples from the Hesperides, for he did not acknowledge the labour of the cattle of Augeas nor that of the hydra. These apples were not, as some have said, in Libya, but on Atlas among the Hyperboreans. They were presented <by Earth> to Zeus after his marriage with Hera, and guarded by an immortal dragon with a hundred heads, offspring of Typhon and Echidna, which spoke with many and divers sorts of voices. With it the Hesperides also were on guard, to wit, Aegle, Erythia, Hesperia, and Arethusa." [2.5.11]

Of course, nothing is ever easy for our hero. Getting to the apples is harder than getting them! Before he could even get to work, Hēraklēs met Cycnus, a fellow hero, son of Ares . Zeus stopped the battle before it could get out of hand. Traveling on, Hēraklēsfought the sea God Nereus for the location of the garden where the tree of the golden apples stood. He wrestled the location out of the Gods and travelled to Lybia where he was challenged by Antaeus, son of Poseidon, who had the habit of challenging and killing strangers, only Hēraklēs killed him instead. Afterwards, Apollodorus tells us:

"After Libya he traversed Egypt. That country was then ruled by Busiris, a son of Poseidon by Lysianassa, daughter of Epaphus. This Busiris used to sacrifice strangers on an altar of Zeus in accordance with a certain oracle. For Egypt was visited with dearth for nine years, and Phrasius, a learned seer who had come from Cyprus, said that the dearth would cease if they slaughtered a stranger man in honor of Zeus every year. Busiris began by slaughtering the seer himself and continued to slaughter the strangers who landed. So Hercules also was seized and haled to the altars, but he burst his bonds and slew both Busiris and his son Amphidamas.

And traversing Asia he put in to Thermydrae, the harbor of the Lindians. And having loosed one of the bullocks from the cart of a cowherd, he sacrificed it and feasted. But the cowherd, unable to protect himself, stood on a certain mountain and cursed. Wherefore to this day, when they sacrifice to Hercules, they do it with curses.

And passing by Arabia he slew Emathion, son of Tithonus, and journeying through Libya to the outer sea he received the goblet from the Sun. And having crossed to the opposite mainland he shot on the Caucasus the eagle, offspring of Echidna and Typhon, that was devouring the liver of Prometheus, and he released Prometheus, after choosing for himself the bond of olive, and to Zeus he presented Chiron, who, though immortal, consented to die in his stead.

Now Prometheus had told Hercules not to go himself after the apples but to send Atlas, first relieving him of the burden of the sphere; so when he was come to Atlas in the land of the Hyperboreans, he took the advice and relieved Atlas. But when Atlas had received three apples from the Hesperides, he came to Hercules, and not wishing to support the sphere <he said that he would himself carry the apples to Eurystheus>, and bade Hercules hold up the sky in his stead. Hercules promised to do so, but succeeded by craft in putting it on Atlas instead. For at the advice of Prometheus he begged Atlas to hold up the sky till he should put a pad on his head. When Atlas heard that, he laid the apples down on the ground and took the sphere from Hercules. And so Hercules picked up the apples and departed. But some say that he did not get them from Atlas, but that he plucked the apples himself after killing the guardian snake. And having brought the apples he gave them to Eurystheus. But he, on receiving them, bestowed them on Hercules, from whom Athena got them and conveyed them back again; for it was not lawful that they should be laid down anywhere."

According to Hyginus, Ladôn was put into the sky as the constellation Draco.

"This huge serpent is pointed out as lying

between the two Bears. He is said to have guarded the golden apples of the

Hesperides, and after Hercules killed him, to have been put by Juno [Hera] among

the stars, because at her instigation Hercules set out for him. He is considered

the usual watchman of the Gardens of Juno. Pherecydes says that when Jupiter

[Zeus] wed Juno, Terra [Gaea] came, bearing branches with golden applies, and

Juno, in admiration, asked Terra to plant them in her gardens near distant Mount

Atlas. When Atlas’ daughters kept picking the apples from the trees, Juno is

said to have placed this guardian there. Proof of this will be the form of

Hercules above the dragon, as Eratosthenes shows, so that anyone may know that

for this reason in particular it is called the dragon." [II.3]

_07.jpg/763px-Mosaico_Trabajos_H%C3%A9rcules_(M.A.N._Madrid)_07.jpg)