I get a lot of questions from readers, and most of the time, the answers are fairly short. When I feel the question or the reply would be valuable to others as well, I make a post with a collection of them and post them in one go. Today is one of those posts.

"Hey! I'd really like to do short, easy rituals before I study (30 seconds or less) in dedication to Athena/Apollo (or maybe others depending on the situation) and was wondering if you had any ideas? I would mostly like to do something in terms of miniature sacrifice/self cleansing (or something similar) if possible, words never really work so well for me. Thank you so much!!"

Let me first say one thing I think is very important: Hellenismos is a religion that works on

kharis--religious reciprocity. Otherwise put: you get out of it what you put in. So I am not against mini rituals atop of festival celebrations and perhaps daily rituals, but solely mini rituals...? I'm not a big fan. As for not using words: in the ancient Hellenic religion, it was important to raise one's voice when hymns were sung, and especially so when

prayers were made.

That having been said, I suppose it's possible to condense the ritual down to its very bare bones:

- Set out a bowl of water

- Light a candle to Hestia with a match

- Drop the match into the bowl of water and use it as

khernips or make a

weekly batch on Sunday if you really want to.

- Wash your hands and face and flick the access water off over your shrine to cleanse it.

- Say a few words to Hestia. Stick the Homeric Hymn 24 to Hestia on your wall and recite it:

"Blessed Goddess Hestia, you who tend the holy house of the lord Apollo, the Far-shooter at goodly Pytho, with soft oil dripping ever from your locks, come now into this house, come, having one mind with Zeus the all-wise—draw near, and withal bestow grace upon my song."

- Pour some wine out to Hestia (straight out of the bottle into the khernips bowl if you have to. This will dilute it, as it is supposed to be sacrificed).

- Recite a hymn to Athena/Apollon. You can pick a short one if you'd like and stick it up to your wall next to the hymn to Hestia.

- Pour some wine out to Athena/Apollon (straight out of the bottle into the khernips bowl if you have to. This will dilute it, as it is supposed to be sacrificed).

- Say your prayers.

- Blow out the candle and clean up.

I just tried it and it took me one minute and twenty-one seconds. Since thirty seconds is... not enough for pretty much anything, I'd say that is a fairly short ritual. Again, I am not a fan, but it will work.

~~~

"Hey so I was thinking about the offering the coin to Charon thing. And I how it isn't wholly the monetary value, but the act of it. And what do you think about a tattoo of a coin? Like just a small little thing so you always have the offering with you and ready to give at a moments notice?"

The ancient Hellenes believed that the moment a person died, their psyche--spirit--left the body in a puff or like a breath of wind. Proper burial was incredibly important to the ancient Hellenes, and to not give a loved one a fully ritualized funeral was unthinkable. It was, however, used as punishment of dead enemies, but only rarely. Funerary rites were performed solely to get the deceased into the afterlife, and everyone who passed away was prepared for burial according to time-honoured rituals. As part of thse rituals, a coin could be presented to the dead, and laid under or below the tongue, or even on the eyes, as payment to Kharon.

This ritual was widespread in literature, but archareological evidence tells us it didn't always happen. In fact, only a small percentage (only about 5 to 10 percent) of known ancient Hellenic burials contain coins. Among these there are widespread examples of a single coin positioned in the mouth of a skull or with cremation remains.

The coin for Kharon is conventionally referred to in Hellenic literature as an obolos (ὀβολός), one of the basic denominations of ancient Hellenic coinage, worth one-sixth of a drachma, or other relatively small-denomination gold, silver, bronze or copper coin in local use. You are, thus, right that it wasn't solely abou the monetary value, but it was definitey something that had to have monetary value. It was also something that you could 'physically' give to Kharon. It as payment, after all: 'I give you this coin and you don't leave me stranded on the banks of the river Akheron to wander around as a shade for all eternity'.

So, the coin was not standard practice, but if you would like to have one, tell your family or have it registered. I'm not sure how it is in other countries, but here in the Netherlands, we have insurance to pay for our funeral when we go. As part of that, we get to fill in our wishes for the funeral itself. Get it recorded that you want to be buried with a coin you buy off the internet, or a low value coin of your local currency, in your mouth. Personally, I don't think a coin tattoo will work, not even if you have it tattooed on your tongue.

~~~

"Do you think it's possible to practice witchcraft and Hellenic polytheism respectfully?"

I... think that depends on your goal. If you mean a Recon approach to Hellenismos coupled with the modern practice of Witchcraft, based on the work of Crowley and Gardner, then no, I do not think that is possible. the two are entirely incompatible. If you want to practice a version of Reformed Hellenic Polytheism combined with modern witchcraft then.... it does not have my personal preference but it could work. If you want to practice Traditional Hellenismos with ancient Hellenic witchcraft then... yeah, I think that could be done respectfully.

Something I often hear about the ancient Hellenic religion, and prescribed about its modern equivalent, is that there was no magic in ancient Hellas. This is true. It's also a lie. It all depends on your definition of magic, and for the purpose of this reply, we are going to see magic as a form of prayer and ritual, conducted outside of the

usual ritual steps. The Theoi were always invoked, but for magic, the sacrifices were usually to the khthonic, or

Underworld Gods.

The ancient Hellenes were a competitive people, and struggled with many of the issues we do today: the urge to perform well, the desire for justice to be served, and a need for love. Prayers for these things were made often, usually in their normal ritualized form at the

house altar. If these requests were made against, or at the expense of another person, however, they were generally taken out of the realm of regular worship and

kharis, and into the realm of the khthonic. The preferred form were

katadesmoi.

Katadesmoi are relatively small tablets, inscribed with a desire asked of the Theoi to fulfil. The Katadesmoi that have survived were generally made out of very thin sheets of lead, which were then rolled, folded or pierced with nails. Wax, papyrus, stone, precious metals, and precious minerals would also have been used as a medium. Some katadesmoi were accompanied by a small doll representing the intended victim or even a lock of their hair, especially in the case of love spells. Katadesmoi were usually deposited where they would be closest to the Underworld: in chasms, pools of water, wells, caves, temples to the deity in question, buried underground, or placed in graves. In general, the katadesmoi always included the name of the intended victim and the name(s) of the appropriated Gods--most often Hades, Kharon, Hekate, and Persephone. Exceptions have been found, of course.

In general, katadesmoi were used out of desperation: regular channels had been exhausted, human courts would never convict the perpetrator of a crime, or the murderer could no be found. Pleading with the Gods--who knew more, saw more, had a much farther reach--was considered the only alternative to get justice. This was even the case in many love spells. Katadesmoi were not made willy-nilly: there needed to be a strong incentive to make one.

So I think you can practice witchcraft and Hellenismos, but no, I don't believe modern witchcraft and Hellenismos are compatible and I have

exlained why before.

~~~

"I do oracle readings to communicate to aphro/apollo but I fear that most of my readings can get invaded is there a secret password I can use to tell if it's them and how can I do this?"

Yeah... sadly, you can't. I'm curious, though: who or what do you think might 'invade' your readings?

Divination played a fairly large role in Hellenic every day life, even though divination of any kind was rarely turned to to predict the future. To desire knowledge of the future was considered hubris. Instead, oracles and seers were petitioned to help answer questions about the present or to advice on a decision which had to be made in the very near future. 'Shall I go to war?', ' Shall I put my sheep out on the high pasture?'. Most often, oracular questions were posed in a way which made it easy for the God(dess)--and the seer--to answer; they did not ask 'Shall I go to war?', they asked 'Don't you think I ought to go to war?'. Most likely, the answer of seers (and perhaps even oracles) depended on the offertory; if it was large enough, the answer was 'yes', if the offertory was dissatisfactory, the answer would be 'no'.

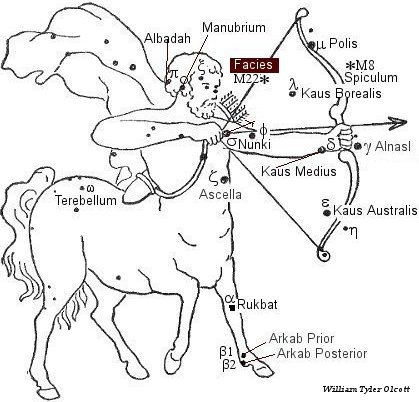

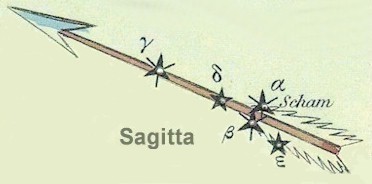

Oracles given directly, like at Delphi, were rare and called chesmomancy. All other forms of divination practiced in ancient Hellas were performed by seers, not oracles. Seer staples were divination through the spotting of birds (ornithomancy and augury), dream interpretation (oneiromancy) and animal sacrifice (hieromancy, haruspicy, empyromancy and extispicy) but other forms of divination were definitely used, including cledonomancy (listening to words spoken by a crowd), oneiromancy (divination through the reading of birthmarks) and Phyllorhodomancy, the reading of the sound rose petals make when slapping them together with your hands. The biggest difference between oracles and seers was that oracles gave long answers which usually needed some for of interpretation while seers usually answered yes-or-no questions.

Many divinatory practices remain today but most modern Hellenics divine differently than the Hellens of old. Tarot has become a staple in divination, for example. On very, very, very, rare occasions I do

divinatory readings for myself or others, though mostly for others. These readings are done with my Olympus Tarot or through

ornithomancy, something I am still developing but which I am slowly getting better at. Reading is morally complicated for me. It is hard to balance the line between helpful and hubris. I'm not an oracle, I'm not even a seer. At most I am someone with good meditative abilities and a pack of tarot cards I can read instinctively. I have very clear ideas on the

interpretation of signs and they always play through my mind before I start. Once I start reciting hymns, though, and giving sacrifice, my doubts fade. There is no room for them.

At the end of the day, you present your reading and you hope it's truthful. That whoever gave it decided to give you the (full) truth and that you interpreted things correctly. There is a reason I think divination of any type is not something to be messed with and taken as advice at best: you never truly know how much truth is in it.

_-_Walters_48225.jpg)