In Aristophanes’ comedy The Frogs, a nosy slave listens to his master’s conversations and spreads them around town, resulting in his master’s horrible misfortunes. The Aristophanes character, however, was not put there just for laughs. Gossip was a real tool in the hands of serfs who wanted to punish their masters if they had treated them badly in ancient Hellas.

Masters were justifiably worried that a slave might see or hear something in the household which could end up being used against them in a court of law or public opinion. There is even a Goddess who has gossip as her domain:Pheme (“fame” or “rumor” in English), daughter of Gaia. She was depicted as a terrible winged creature who delighted in ruffling her feathers. Beneath every feather there was a prying eye, a pricked ear and a wagging tongue. She flew from place to place at great speed, gabbling and screeching lies and half-truths to any person who would listen.

Idle gossip was a favorite pastime in ancient Hellas, as many historians have attested. People from all walks of life constantly indulged in sharing hearsay, rumors and half-truths. Serfs and low-status women without strong family connections could use gossip as their only weapon against their enemies. This propensity to gossip in almost every member of society served to open up conduits between the weak and the strong, the rich and the poor, the master and the servant.

The great philosopher Aristotle viewed gossiping as a frequently trivial, enjoyable pastime, but also saw that gossiping could have malicious intent when spoken by someone who has been wronged. Malicious gossip could damage a person’s reputation and irreparably hurt him or her.

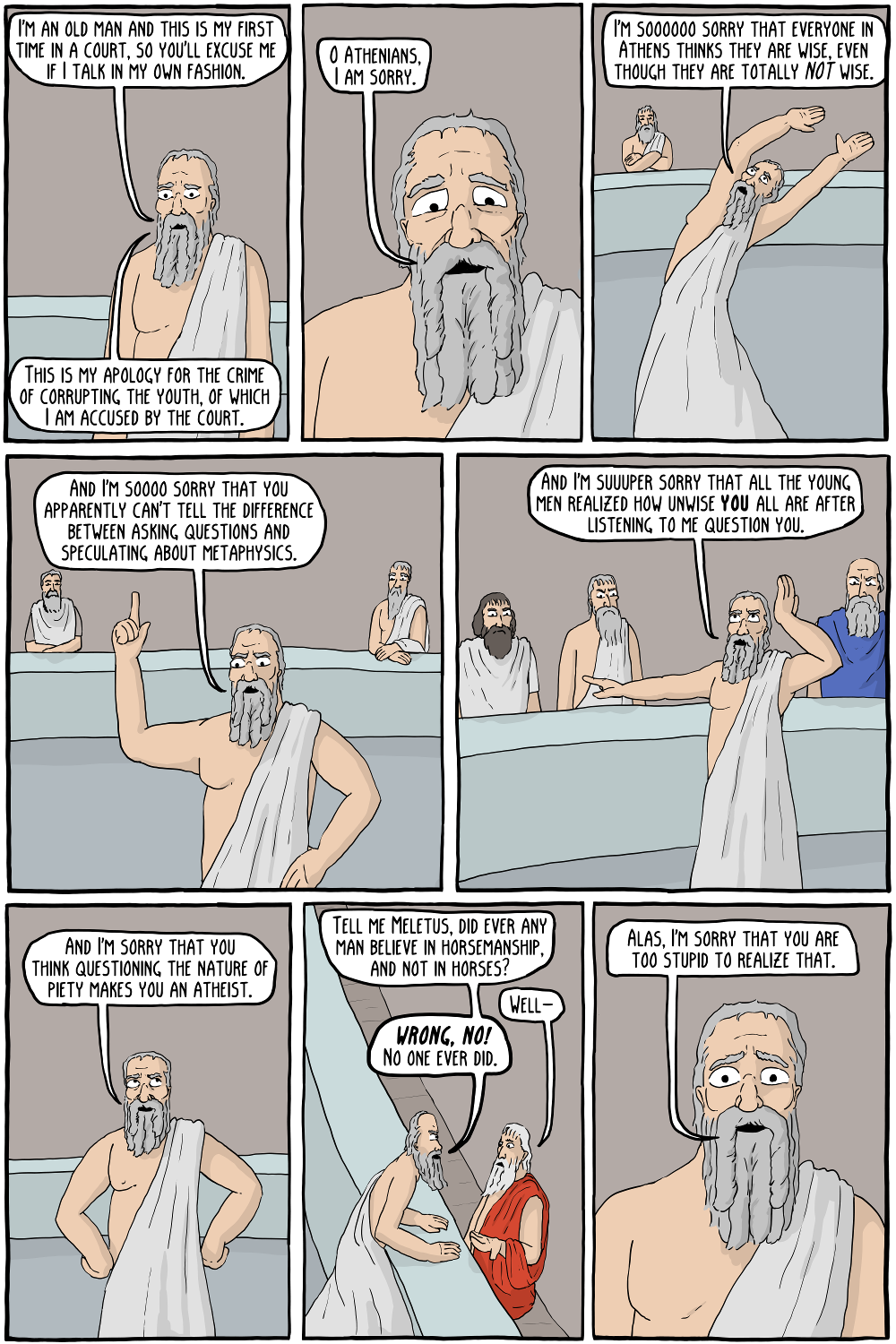

In ancient Athens, court decisions were based heavily on a character evaluation of the defendant and very little on hard evidence. Therefore, an individual’s reputation was important when it came to judicial cases. In the absence of professional judges, speakers aimed to discredit their opponents’ characters in the eyes of the jurors, while presenting themselves as upstanding citizens.

The power of gossip was feared by litigants, so they carefully outlined how the negative stories the jurors might have heard about them weren’t true, and had been spread intentionally by their opponents. Because of the great crowds which gathered there, public places such as the Agora were prime locations to spread gossip and outright lies aimed at discrediting an opponent. In these instances, the intention of the gossipers was to spread false information across the city to generate an impression of the individuals involved which would help them win their legal cases.

In ancient Athens, women had few legal rights and depended on male relatives to act for them. However, women had one very powerful outlet – gossip – to serve as a useful tool in attacking an enemy.

Women’s gossip was used effectively to discredit the character of an opponent in court. Low-status women, with absolutely no access to legal help, could still use gossip to help achieve retribution when they were wronged.

The presence of gossip in legal cases shows that Athenians did not discriminate about the source, but freely took advantage of all kinds of rumors and innuendo in their attempts to defeat their adversaries.

Through calculated use of gossip, women, non-citizens and even serfs with no access to official legal channels whatsoever in ancient Hellas wielded a potent weapon in their attempts to attain justice against those who had wronged them.

Socrates, one of the greatest Hellenic philosophers, who lived from 469 – 399 BC, shunned gossip. It is said that one day he came upon an acquaintance who ran up to him excitedly and said, “Socrates, do you know what I just heard about one of your students?”

“Wait a moment,” Socrates replied. “Before you tell me I’d like you to pass a little test. It’s called the Triple Filter Test.”

“Triple filter?” his friend asked.

“That’s right,” Socrates continued. “Before you talk to me about my student let’s take a moment to filter what you’re going to say. The first filter is Truth. Have you made absolutely sure that what you are about to tell me is true?”

“No,” the man said, “actually I just heard about it and…”

“All right,” said Socrates. “So you don’t really know if it’s true or not. Now let’s try the second filter, the filter of Goodness. Is what you are about to tell me about my student something good?”

“No, on the contrary… “

“So,” Socrates continued, “you want to tell me something bad about him, even though you’re not certain it’s true?” The man shrugged, a little embarrassed. Socrates continued. “You may still pass the test though, because there is a third filter – the filter of Usefulness. Is what you want to tell me about my student going to be useful to me?”

“No, not really,” the man admitted.

“Well,” concluded Socrates, “if what you want to tell me is neither True nor Good nor even Useful, why tell it to me at all?”

The man who had tried to spread gossip to the great thinker was defeated and ashamed.