A very good friend of mine lost someone tonight, and came to me for spiritual advice on how to deal with this grief. He is not Hellenistic, but values the lessons of Hellenismos on life and religion, and as such, he wanted to hear about funerary traditions within Hellenismos, and ancient Hellenic practice. What came out what a bit of a rambled Facebook message that was vague enough for interpretation but was anywhere from complete. As such, I write this today--in a hurry before an appointment--with love and sorrow in my heart, for a friend who suffers, and a young girl who lost her life.

The ancient Hellenes believed that the moment a person died, their psyche--spirit--left the body in a puff or like a breath of wind. Proper burial was incredibly important to the ancient Hellenes, and to not give a loved one a fully ritualized funeral was unthinkable. It was, however, used as punishment of dead enemies, but only rarely. Funerary rites were performed solely to get the deceased into the afterlife, and everyone who passed away was prepared for burial according to time-honored rituals.

A burial or cremation had four parts: preparing the body, the prothesis (Προθησις, 'display of the body'), the ekphorá (ἐκφορά 'funeral procession'), and the interment of the body or cremated remains of the deceased. Preparation of the body was always done by women, and was usually done by a woman over sixty, or a close relative who was related no further away from the deceased than the degree of second cousin. These were also the only people in the ekphorá. The deceased was stripped, washed, anointed with oil, and then dressed in his or her finest clothes. They also received jewelry and other fineries. A coin could be presented to the dead, and laid under or below the tongue, or even on the eyes, as payment to Kharon.

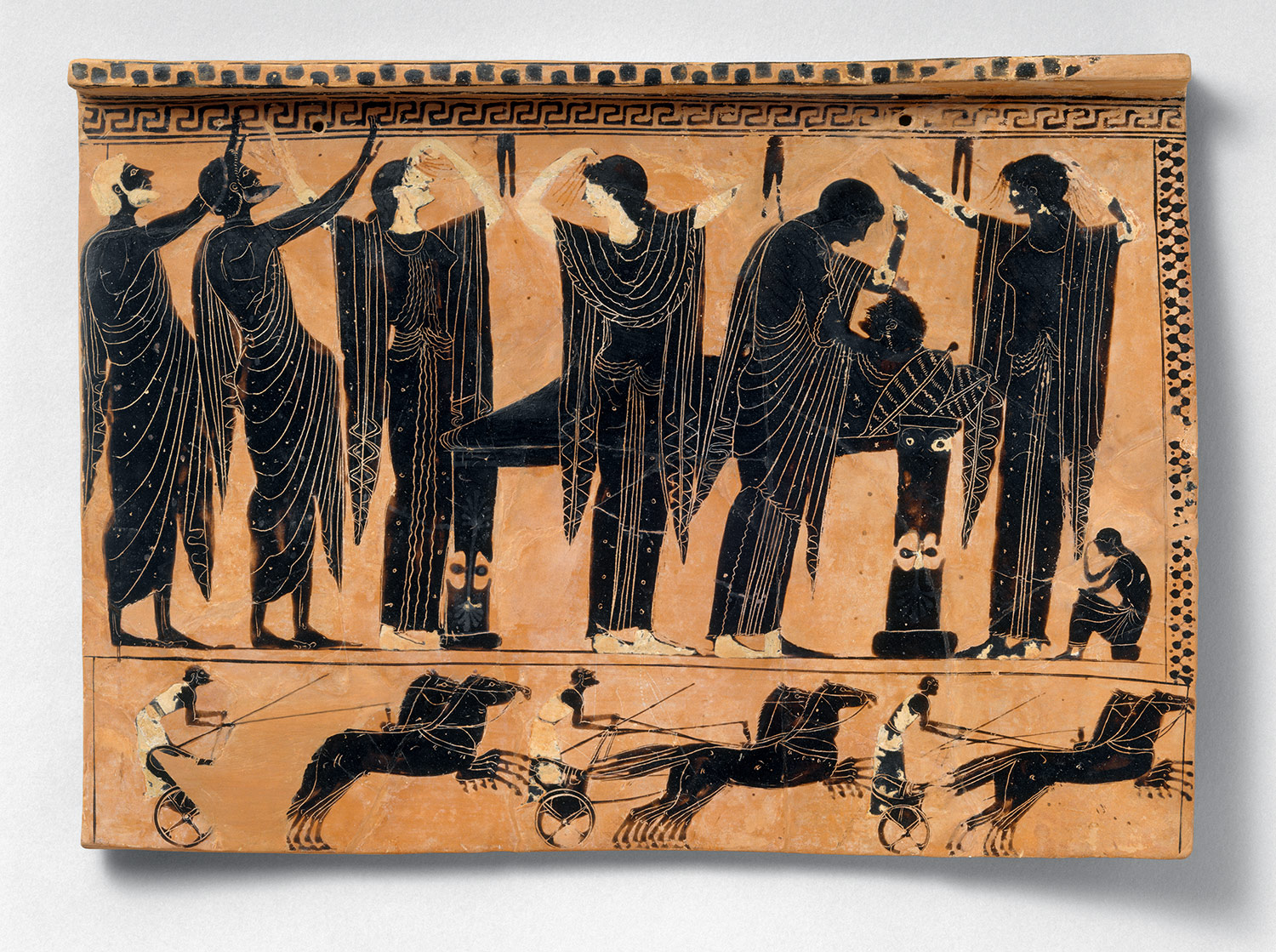

During the prothesis, the body was put out in the courtyard for a day, placed on a bier (as seen on the funerary plaque to the right). Relatives and friends came to mourn and pay their respects. Everyone, but women especially, grieved loudly and respectfully. It was possible to hire professional keeners, who sang ritualized laments and dirges, tore at their hair and pounded their chests in lamentation of the dead. The more grief was shown, the higher the level of respect for the dead.

Right before sun up on the next day, the ekphorá took place. At this time of day, not too many people were outside yet, and this way, miasma was limited to only the grieving family. Women played a major role in funerary rites, a much bigger role than men, but both walked the procession. Men cremated or inhumed the body and gave the final offerings. They also, obviously, constructed the tomb or grave. Men led the way to the cemetery--carrying the bier--followed by the women, and then the children. There was a flute player who served as an indicator that there was a funeral going on, so other inhabitants of the city or village could avoid miasma.

After arriving at the tomb or cemetery, the women turned back, most likely to prepare a large supper at home, and certainly to purify it. The men remained and burned the body (a mostly Athenian practice) or otherwise set up the body. A related mourner first dedicated a lock of hair, then provided the deceased with offerings of honey, milk, water, wine, perfumes, and oils mixed in varying amounts. Any libation was a khoe; a libation given in its entirety to the deceased. None was had by the mourners. A prayer to the Theoi--most likely Hermes Khthonios--then followed these libations. It was also possible to make a haimacouria before the wine was poured. In a haimacouria, a black ram or black bull is slain and the blood is offered to the deceased. This blood sacrifice, however, was probably used only when they were sacrificing in honor of a number of men, or for someone incredibly important. Then came the enagismata, which were offerings to the dead that included milk, honey, water, wine, celery, pelanon--a mixture of meal, honey, and oil--and kollyba--the first fruits of the crops and dried fresh fruits.

Unlike the ancient Egyptians, the ancient Hellenes placed very few objects in the grave, but monumental earth mounds, rectangular built tombs, and elaborate marble stelai and statues were often erected to mark the grave and to ensure that the deceased would not be forgotten. Grave gifts were allowed in many places, but could not cost more than a set amount all together. These elaborate burial places served as a place for the family members to visit the grave with offerings that included small cakes and libations. The goal was to never be forgotten; if the dead was remembered always, and fed with libations and other offerings, their spirit would stay 'alive' forever. That said, especially in Athens, names on grave markers were restricted to women who died in childbirth and men who died in battle.

After the burial, the family stayed in mourning for a month. During this time, or perhaps a little less long, they were ritually polluted due to exposure to the underworld through the deceased. As such, they could not take part in festivals, nor offer to the Theoi, nor visit temples. They would frequent the grave or tomb often, however, and present the dead with khoes and burnt sacrifice of cakes and fruit.

So, how do we perform these rites when our loved ones are not Hellenistic? How do we give them the best Hellenic chance in the afterlife, or deal with our personal grief in a religion that was not their own? And what if it was their own, how do we deal with it then? Many modern funeral rites bear striking resemblance to the customs of the ancient Hellenes. The body is washed and cleaned, then laid out to be visited. There is often a procession to the burial place or crematorium. We are still allowed and encouraged to show our grief during the funeral or cremation. There is always a place where the deceased can be visited; either a grave, a field where the ashes were strew out, or an urn. Some funeral homes allow family members to help with washing and dressing of the deceased, and you can pretty much request anything you want in your own will, including the inclusion of a coin.

At home, when you are not actively involved in the funerary rites, you can still make the khoe to Hermes Khthonios, and present him with coin(s) for the dead. Tell him you will pay for their passage, should they need it, and pray that He and Kharon will accept. Grieve loudly, especially if you are a woman. Tell stories of the deceased, and make sure they are never forgotten. After the funeral or cremation, cleanse yourself and the house thoroughly. I would not recommend bringing the ashes of the deceased home with you, as this would permanently pollute the house.

I feel for my friend who lost someone, and for her family. May Hermes Khthonios carry this girl safely to where she wants to be, and may the Theoi look kindly upon the mourners. Ease their suffering and alleviate their pain. May the deceased always be remembered, and live on through story and laughter.

Image source: attic funerary plaque

The ancient Hellenes believed that the moment a person died, their psyche--spirit--left the body in a puff or like a breath of wind. Proper burial was incredibly important to the ancient Hellenes, and to not give a loved one a fully ritualized funeral was unthinkable. It was, however, used as punishment of dead enemies, but only rarely. Funerary rites were performed solely to get the deceased into the afterlife, and everyone who passed away was prepared for burial according to time-honored rituals.

A burial or cremation had four parts: preparing the body, the prothesis (Προθησις, 'display of the body'), the ekphorá (ἐκφορά 'funeral procession'), and the interment of the body or cremated remains of the deceased. Preparation of the body was always done by women, and was usually done by a woman over sixty, or a close relative who was related no further away from the deceased than the degree of second cousin. These were also the only people in the ekphorá. The deceased was stripped, washed, anointed with oil, and then dressed in his or her finest clothes. They also received jewelry and other fineries. A coin could be presented to the dead, and laid under or below the tongue, or even on the eyes, as payment to Kharon.

During the prothesis, the body was put out in the courtyard for a day, placed on a bier (as seen on the funerary plaque to the right). Relatives and friends came to mourn and pay their respects. Everyone, but women especially, grieved loudly and respectfully. It was possible to hire professional keeners, who sang ritualized laments and dirges, tore at their hair and pounded their chests in lamentation of the dead. The more grief was shown, the higher the level of respect for the dead.

Right before sun up on the next day, the ekphorá took place. At this time of day, not too many people were outside yet, and this way, miasma was limited to only the grieving family. Women played a major role in funerary rites, a much bigger role than men, but both walked the procession. Men cremated or inhumed the body and gave the final offerings. They also, obviously, constructed the tomb or grave. Men led the way to the cemetery--carrying the bier--followed by the women, and then the children. There was a flute player who served as an indicator that there was a funeral going on, so other inhabitants of the city or village could avoid miasma.

After arriving at the tomb or cemetery, the women turned back, most likely to prepare a large supper at home, and certainly to purify it. The men remained and burned the body (a mostly Athenian practice) or otherwise set up the body. A related mourner first dedicated a lock of hair, then provided the deceased with offerings of honey, milk, water, wine, perfumes, and oils mixed in varying amounts. Any libation was a khoe; a libation given in its entirety to the deceased. None was had by the mourners. A prayer to the Theoi--most likely Hermes Khthonios--then followed these libations. It was also possible to make a haimacouria before the wine was poured. In a haimacouria, a black ram or black bull is slain and the blood is offered to the deceased. This blood sacrifice, however, was probably used only when they were sacrificing in honor of a number of men, or for someone incredibly important. Then came the enagismata, which were offerings to the dead that included milk, honey, water, wine, celery, pelanon--a mixture of meal, honey, and oil--and kollyba--the first fruits of the crops and dried fresh fruits.

Unlike the ancient Egyptians, the ancient Hellenes placed very few objects in the grave, but monumental earth mounds, rectangular built tombs, and elaborate marble stelai and statues were often erected to mark the grave and to ensure that the deceased would not be forgotten. Grave gifts were allowed in many places, but could not cost more than a set amount all together. These elaborate burial places served as a place for the family members to visit the grave with offerings that included small cakes and libations. The goal was to never be forgotten; if the dead was remembered always, and fed with libations and other offerings, their spirit would stay 'alive' forever. That said, especially in Athens, names on grave markers were restricted to women who died in childbirth and men who died in battle.

After the burial, the family stayed in mourning for a month. During this time, or perhaps a little less long, they were ritually polluted due to exposure to the underworld through the deceased. As such, they could not take part in festivals, nor offer to the Theoi, nor visit temples. They would frequent the grave or tomb often, however, and present the dead with khoes and burnt sacrifice of cakes and fruit.

So, how do we perform these rites when our loved ones are not Hellenistic? How do we give them the best Hellenic chance in the afterlife, or deal with our personal grief in a religion that was not their own? And what if it was their own, how do we deal with it then? Many modern funeral rites bear striking resemblance to the customs of the ancient Hellenes. The body is washed and cleaned, then laid out to be visited. There is often a procession to the burial place or crematorium. We are still allowed and encouraged to show our grief during the funeral or cremation. There is always a place where the deceased can be visited; either a grave, a field where the ashes were strew out, or an urn. Some funeral homes allow family members to help with washing and dressing of the deceased, and you can pretty much request anything you want in your own will, including the inclusion of a coin.

At home, when you are not actively involved in the funerary rites, you can still make the khoe to Hermes Khthonios, and present him with coin(s) for the dead. Tell him you will pay for their passage, should they need it, and pray that He and Kharon will accept. Grieve loudly, especially if you are a woman. Tell stories of the deceased, and make sure they are never forgotten. After the funeral or cremation, cleanse yourself and the house thoroughly. I would not recommend bringing the ashes of the deceased home with you, as this would permanently pollute the house.

I feel for my friend who lost someone, and for her family. May Hermes Khthonios carry this girl safely to where she wants to be, and may the Theoi look kindly upon the mourners. Ease their suffering and alleviate their pain. May the deceased always be remembered, and live on through story and laughter.

Image source: attic funerary plaque

-

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

ancient Hellenic culture Hellenismos 101 Hermes Khthonios Kharon personal

6 comments:

great blog, I my sympathies go to your friends family. May hermes guide her sould through the underworld and show her the way to where she needs to go. May she find her place in elysium :)

@UltravioletAngel: Thank you, much appreciated.

Thank you so much for this post. I traveled last weekend to say good bye to my mother as she is in her last weeks of life. I won't be able to make it back for the funeral so I was wondering what I could do up here to properly grieve her and find closure. And as it looks like my father may be in his last days as well, your post if very timely for me. A gift from the gods in a way.

I'm very sorry your friend has suffered such a loss. May Persephone whisper in Hades's ear and tell him of the love her friend has for her.

@Kathy: I am grateful I got to offer you a little bit of relief in your trying time. My the Theoi watch over you and grant gentile repose to your parents. May they be judged fairly and be blessed.

Thank you, Elani.

great post :) A friend of mine in Hellas said that the soul is attached to the earth for 40 days before Hermes retrieves it. I found this in Pausanias, yet he says 30 days. He references it particularly for Arkadia, but I find the practice to make sense to me. For 30 days the soul is in the possession of Apollon as god of the cemetery (he is given first offerings at the burial probably due to his associations with death and the decomposition process), and then after 30 days the family comes and gives offerings to Hermes who then retrieves the souls of the dead.

Post a Comment