We are still a long way's away from the next Olympics, bur the 'R'is a difficult letter when you are solely interested in ancient Hellas, so I'm being creative with both my title and choice of subject. Today, I want to talk about the ancient Panhellenic games, of which the Olympic Games were the most famous part. Before I do that, however, I need to make a disclaimer and say that my tablet PC bricked up on me last night, so I am typing this on a computer without spell checker. I'm sorry if errors slip in.

It is important to note that the most important events at the Games weren't the sport events; they were the sacrifices, offerings and other dedicatory practices which were continually performed during the (first one day, then three days, then) five day event. Depending on the location, there were also artistic happenings; writers, sculptures and painters showed what they could do in their given trade. Palmistry was practiced, wine flowed freely and there were a lot of prostitutes, who made more money in these five days than in the whole of a year without the sporting event. The Games were festivals unlike any other.

Of course, the sporting events had a special place during the Games; they were the biggest part of the entertainment, after all. Unlike the winners of the Panathenaic sporting events, however, winners of the Games got rather minor rewards: Olympic winners recieved a garland of olives, Pythian winners recieved a laurel wreath, Nemean winners recieved a wild celery garland and the Isthmian winner recieved a pine garland. Prizes for winners of speciffic matches and races were, however, rewarded, and winners were lauded as heroes, and once home, they woud never have to work again.

Especially towards the end of the Games, there was great variety in sporting events, although not as much as the modern Olympics give us. Today, I want to discuss these various sports.

Harmatodromia (ἁρματοδρομία) - Harmatodromia, or chariot racing, was one of the most popular ancient Hellenic sports. In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, there were both four-horse (tethrippon, τέθριππον) and two-horse (synoris, συνωρὶς) chariot races. Distances varied according to the event. The chariot racing event was first added to the Olympics in 680 BC with the games expanding from a one-day to a two-day event. We don't know when they were added to the other Panhellenic games, but probably around the same time or a little later.

Hómēros in his Iliad describes a chariot race in vivid detail:

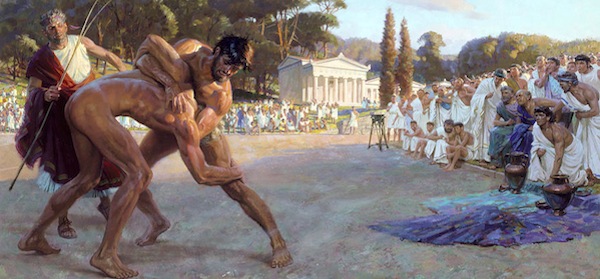

Pankration (παγκράτιον) - This rough contact sport was a combination of boxing and wrestling. Biting and gouging an opponent's eyes, nose, or mouth with fingernails was not allowed, but everything else was allowed. Deaths happened. Unlike at the boxing competitions, the fighters did not wrap their hands, so it was a bare knuckle fight.Like the other combat sports, a fighter could surrender or fight until knock out. Pankration was not a free-for-all, though; fighters were in excellent form, and there were a large variety of fighting stances and techniques. In fact, many of these are still known, or have been reconstructed and especially in modern Greece, pankration is a sport you can take part in today.

Pentathlon (πένταθλον) - A pentathlon incruded a combination of five separate disciplines: discus, javelin, jump, running, and wrestling. The event was first held at the 18th Ancient Olympiad, around 708 BC. The discus throw was similar to the modern event, with the implement made from stone, iron, bronze, or lead. The javelin event was also similar to the modern event, although the javelin was made of wood and had a thong for attaching the thrower's fingers. Unlike in the modern jumping events, the participants held onto lead or stone jump weights (called halteres (ἁλτῆρες)) which were thrown backwards during the jump to propel them forward and increase the length of their jump. Halteres were made of stone or metal, and weighed between 12 and 35 kg (26 and 77 lb).

The running event was called the 'stadion' (στάδιον), and was a a 200-yard (about 180-metre) sprint. From the years 776 to 724 BC, the stadion was the only event that took place at the Olympic Games and the victor gave his name to the entire four-year Olympiad. This allows scholars to know the names of nearly every ancient Olympic stadion winner. For a description of the wrestling matches, see 'Pále' above.

Pygmachia (Πυγμαχία, 'fist fighting') - Pygmachia, or boxing, was a brutal sport, and had few rules. There were no rounds, and if an opponent was down, he was fair game. Also, the fighters were chosen by lot, and there were no weight categories: if luck was not at your side, you could end up facing a much heavier opponent. Winners were declared by K.O. of the other fighter, or if the other fighter surrendered. Instead of gloves, ancient boxers wrapped leather thongs called 'himantes' around their hands and wrists which left their fingers free. These were thongs of ox hide approximately 3 to 3.7 meters long that were wrapped around the hands and knuckles for protection and extra punch. Somewhere prior to 400 BC, 'oxys' were introduced to boxing. They consisted of several thick leather bands encircling the hand, wrist, and forearm. A sweatband wrapped around the arm was also added. Around 400 BC 'sphairai' were introduced, which were essentially himantes, but they contained a padded interior and the exterior of the thong was more rigid and hard. The Boxer of Quirinal (depicted left) dated to about 300–200 BC shows these straps.

We actually have a very good description about how these boxing matches would have gone: Hómēros in his Iliad describes the boxing match between Epeius and Euryalus:

Riding - Riding--like the chariot races--were for the wealthy. The winners were not the riders themselves, but the owners of the horse. As such, there were actually women who won equestrian events. In the Olympic riding events, held over 6 laps around the track (about 4.5 miles), the jockeys rode bareback. There were separate races for adult horses and foals.

Running - The Olympic Games originally contained one event: the stadion (or "stade") race, a short sprint the length of the stadium. Runners had to pass five stakes that divided the lanes: one stake at the start, another at the finish, and three stakes in between.

The Diaulos (Δίαυλος), or two-stade race, was introduced in 724 BC, during the 14th Olympic games. The race was a single lap of the stadium, approximately 400 metres (1,300 ft), a turn around a post (either an individual one, or a single one) and then the return journey.

A third foot race, the Dolichos (Δόλιχος), was introduced in 720 BC. The length of the race was somewhere between 18–24 laps, or about three miles (5 km). At Olymia, the race started and ended at the stadium, but then wound its way throughout the grounds, passing by important shrines and statues, including the Nike statue by the temple of Zeus. This race was closest to our modern marathon.

The last running event added to the Olympic program was the Hoplitodromos (Ὁπλιτόδρομος), or 'Hoplite race', introduced in 520 BC and traditionally run as the last race of the Olympic Games. The runners would run either a single or double diaulos (see above) in full or partial armour, carrying a shield and additionally equipped either with greaves or a helmet. The armor was a huge hindrance for the otherwise bare runners, as an armor avaraged out between 50 and 60 lb (27 kg). Although many events on the Games were throwbacks to war, the hoplitodromos emulated the speed and stamina needed for warfare. As depicted to the side, runners sometimes dropped their shields because of the weight, and runners would have to jump over it to keep from falling.

From Hómēros, we again have a description:

The Panhellenic games were a cycle of four large sporting events. The Olympic Games were held every four years, like they are now, from 776 B.C. to A.D. 394, were dedicated to Zeus, and were held in Olympia, Elis. The Pythian Games were dedicated to Apollon, were held in Delphi and were held every four years, starting three years after the Olympic Games. The Nemean Games were dedicated to Zeus also, were held in Nemea, Corinthia, and were held every two years. Lastly, the Isthmian Games were dedicated to Poseidon, were held in Corinth, and were also held every two years.

It is important to note that the most important events at the Games weren't the sport events; they were the sacrifices, offerings and other dedicatory practices which were continually performed during the (first one day, then three days, then) five day event. Depending on the location, there were also artistic happenings; writers, sculptures and painters showed what they could do in their given trade. Palmistry was practiced, wine flowed freely and there were a lot of prostitutes, who made more money in these five days than in the whole of a year without the sporting event. The Games were festivals unlike any other.

Of course, the sporting events had a special place during the Games; they were the biggest part of the entertainment, after all. Unlike the winners of the Panathenaic sporting events, however, winners of the Games got rather minor rewards: Olympic winners recieved a garland of olives, Pythian winners recieved a laurel wreath, Nemean winners recieved a wild celery garland and the Isthmian winner recieved a pine garland. Prizes for winners of speciffic matches and races were, however, rewarded, and winners were lauded as heroes, and once home, they woud never have to work again.

Especially towards the end of the Games, there was great variety in sporting events, although not as much as the modern Olympics give us. Today, I want to discuss these various sports.

Harmatodromia (ἁρματοδρομία) - Harmatodromia, or chariot racing, was one of the most popular ancient Hellenic sports. In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, there were both four-horse (tethrippon, τέθριππον) and two-horse (synoris, συνωρὶς) chariot races. Distances varied according to the event. The chariot racing event was first added to the Olympics in 680 BC with the games expanding from a one-day to a two-day event. We don't know when they were added to the other Panhellenic games, but probably around the same time or a little later.

Hómēros in his Iliad describes a chariot race in vivid detail:

"As one, they raised their whips, shook the reins, and urged their teams on. Swiftly the horses galloped over the plain, leaving the ships behind. A whirlwind cloud of dust rose to their chests, and their manes streamed in the wind. Now the chariots ran freely over the solid ground, now they leapt in the air, while the hearts of the charioteers beat fast as they strove for victory, and they shouted to their horses, flying along in the storm of dust.

It was not till the galloping horses were heading back towards the grey sea that each team showed its mettle, and the charioteers forced the pace. Eumelus’ swift-footed mares shot to the front, chased by Diomedes’ stallions, hot on their heels, as if they might mount Eumelus’ chariot, and their heads were at his back as they flew, blowing hot breath on his neck and shoulders. Diomedes would have passed him now, or at least drawn level, if Phoebus Apollo in resentment had not struck the gleaming whip from his hand. Diomedes saw the mares run on, while his own horses slowed without the effect of the whip, and tears of anger filled his eyes. But Athene saw that Apollo had interfered, and speeding after, returned the whip and inspired the team. Then in her anger she chased down Eumelus, and shattered the yoke of his chariot, so the mares swerved from side to side and the broken pole struck the ground, while Eumelus himself was hurled to the earth beside the wheel. The skin was stripped from his elbows, nose and cheeks, his forehead bruised, while his eyes filled with tears and he was robbed of speech.

Meanwhile Diomedes passed the wreck and drove his powerful horses on, far in the lead. Athene had strengthened his team and given him the glory. And red-haired Menelaus, the son of Atreus, ran second. But Antilochus called to his father’s team: ‘On now, show me how you can run. You’ll not catch Diomedes’ pair, for Athene grants them strength and him the glory. But chase down Menelaus’ team, don’t let them beat you, or Aethe the mare will put you to shame. Why so slow, my beauties? I’ll tell you this, if we win a lesser prize, there’ll be no sweet fodder at Nestor’s hands, he’ll slit your throats with his keen blade. So on, as fast as you can, and I’ll contrive to pass them where the course narrows: that’s my chance.’

With this the horses, responding to his threat, speeded up for a while, and soon the steadfast Antilochus saw a narrow place in the sunken road ahead, where a stream swollen by winter rain had eroded the track and hollowed out the course. Menelaus drove on assuming no one could overtake, but Antilochus veered alongside, almost off the track. Then Menelaus called to him, in alarm: ‘Rein in Antilochus, that’s recklessness! The track’s wider further on. Pass there if you can, mind my chariot, don’t wreck us both!’

He shouted loud enough, but Antilochus, pretending not to hear, plied his whip and drove the more wildly. They ran side by side a discus length, as far as a young athlete testing his strength can hurl it from the shoulder, then Menelaus held back, and his pair gave way, fearing the teams might collide and overturn the light chariots, hurling their masters in the dust, for all their eagerness to win. Red-haired Menelaus stormed at Antilochus: ‘You’re a pest Antilochus, we Achaeans credited you with more sense. All the same, you’ll not win a prize, when I force you to answer on oath to this.’

With that he addressed his team: ‘Don’t flag, and don’t lose heart. Their legs will weaken sooner than yours, they’re carrying more years.’ And his pair, responding to his call, increased their speed and closed on the pair in front.

[...] Diomedes soon arrived, whipping the high-stepping horses hard, as they sped towards the goal. Showers of dust clung to him, and the wheel rims hardly left a trace on the powdery ground, as the swift-footed pair flew onwards pulling the chariot, decorated with gold and tin. He drew to a halt in the centre of the ring, sweat pouring to the ground from his horses’ chests and necks. He himself leapt to the ground from his gleaming chariot, and leant the long whip against the shaft. Nor did his squire Sthenelus lose a moment in claiming the prize, but eagerly his joyful friends led away the women and carried off the eared tripod, while he un-harnessed the horses." [Bk XXIII:362]

Pále (πάλη) - This event was similar to the modern wrestling sport--with three successful throws necessary to win a match. It was the most popular organized sport in Ancient Hellas and was the first competition to be added to the Olympic Games that was not a footrace. It was added in 700 BC. An athlete needed to throw his opponent on the ground, landing on a hip, shoulder, or back for a fair fall. Biting and genital holds were illegal.It was not till the galloping horses were heading back towards the grey sea that each team showed its mettle, and the charioteers forced the pace. Eumelus’ swift-footed mares shot to the front, chased by Diomedes’ stallions, hot on their heels, as if they might mount Eumelus’ chariot, and their heads were at his back as they flew, blowing hot breath on his neck and shoulders. Diomedes would have passed him now, or at least drawn level, if Phoebus Apollo in resentment had not struck the gleaming whip from his hand. Diomedes saw the mares run on, while his own horses slowed without the effect of the whip, and tears of anger filled his eyes. But Athene saw that Apollo had interfered, and speeding after, returned the whip and inspired the team. Then in her anger she chased down Eumelus, and shattered the yoke of his chariot, so the mares swerved from side to side and the broken pole struck the ground, while Eumelus himself was hurled to the earth beside the wheel. The skin was stripped from his elbows, nose and cheeks, his forehead bruised, while his eyes filled with tears and he was robbed of speech.

Meanwhile Diomedes passed the wreck and drove his powerful horses on, far in the lead. Athene had strengthened his team and given him the glory. And red-haired Menelaus, the son of Atreus, ran second. But Antilochus called to his father’s team: ‘On now, show me how you can run. You’ll not catch Diomedes’ pair, for Athene grants them strength and him the glory. But chase down Menelaus’ team, don’t let them beat you, or Aethe the mare will put you to shame. Why so slow, my beauties? I’ll tell you this, if we win a lesser prize, there’ll be no sweet fodder at Nestor’s hands, he’ll slit your throats with his keen blade. So on, as fast as you can, and I’ll contrive to pass them where the course narrows: that’s my chance.’

With this the horses, responding to his threat, speeded up for a while, and soon the steadfast Antilochus saw a narrow place in the sunken road ahead, where a stream swollen by winter rain had eroded the track and hollowed out the course. Menelaus drove on assuming no one could overtake, but Antilochus veered alongside, almost off the track. Then Menelaus called to him, in alarm: ‘Rein in Antilochus, that’s recklessness! The track’s wider further on. Pass there if you can, mind my chariot, don’t wreck us both!’

He shouted loud enough, but Antilochus, pretending not to hear, plied his whip and drove the more wildly. They ran side by side a discus length, as far as a young athlete testing his strength can hurl it from the shoulder, then Menelaus held back, and his pair gave way, fearing the teams might collide and overturn the light chariots, hurling their masters in the dust, for all their eagerness to win. Red-haired Menelaus stormed at Antilochus: ‘You’re a pest Antilochus, we Achaeans credited you with more sense. All the same, you’ll not win a prize, when I force you to answer on oath to this.’

With that he addressed his team: ‘Don’t flag, and don’t lose heart. Their legs will weaken sooner than yours, they’re carrying more years.’ And his pair, responding to his call, increased their speed and closed on the pair in front.

[...] Diomedes soon arrived, whipping the high-stepping horses hard, as they sped towards the goal. Showers of dust clung to him, and the wheel rims hardly left a trace on the powdery ground, as the swift-footed pair flew onwards pulling the chariot, decorated with gold and tin. He drew to a halt in the centre of the ring, sweat pouring to the ground from his horses’ chests and necks. He himself leapt to the ground from his gleaming chariot, and leant the long whip against the shaft. Nor did his squire Sthenelus lose a moment in claiming the prize, but eagerly his joyful friends led away the women and carried off the eared tripod, while he un-harnessed the horses." [Bk XXIII:362]

Pankration (παγκράτιον) - This rough contact sport was a combination of boxing and wrestling. Biting and gouging an opponent's eyes, nose, or mouth with fingernails was not allowed, but everything else was allowed. Deaths happened. Unlike at the boxing competitions, the fighters did not wrap their hands, so it was a bare knuckle fight.Like the other combat sports, a fighter could surrender or fight until knock out. Pankration was not a free-for-all, though; fighters were in excellent form, and there were a large variety of fighting stances and techniques. In fact, many of these are still known, or have been reconstructed and especially in modern Greece, pankration is a sport you can take part in today.

Pentathlon (πένταθλον) - A pentathlon incruded a combination of five separate disciplines: discus, javelin, jump, running, and wrestling. The event was first held at the 18th Ancient Olympiad, around 708 BC. The discus throw was similar to the modern event, with the implement made from stone, iron, bronze, or lead. The javelin event was also similar to the modern event, although the javelin was made of wood and had a thong for attaching the thrower's fingers. Unlike in the modern jumping events, the participants held onto lead or stone jump weights (called halteres (ἁλτῆρες)) which were thrown backwards during the jump to propel them forward and increase the length of their jump. Halteres were made of stone or metal, and weighed between 12 and 35 kg (26 and 77 lb).

The running event was called the 'stadion' (στάδιον), and was a a 200-yard (about 180-metre) sprint. From the years 776 to 724 BC, the stadion was the only event that took place at the Olympic Games and the victor gave his name to the entire four-year Olympiad. This allows scholars to know the names of nearly every ancient Olympic stadion winner. For a description of the wrestling matches, see 'Pále' above.

Pygmachia (Πυγμαχία, 'fist fighting') - Pygmachia, or boxing, was a brutal sport, and had few rules. There were no rounds, and if an opponent was down, he was fair game. Also, the fighters were chosen by lot, and there were no weight categories: if luck was not at your side, you could end up facing a much heavier opponent. Winners were declared by K.O. of the other fighter, or if the other fighter surrendered. Instead of gloves, ancient boxers wrapped leather thongs called 'himantes' around their hands and wrists which left their fingers free. These were thongs of ox hide approximately 3 to 3.7 meters long that were wrapped around the hands and knuckles for protection and extra punch. Somewhere prior to 400 BC, 'oxys' were introduced to boxing. They consisted of several thick leather bands encircling the hand, wrist, and forearm. A sweatband wrapped around the arm was also added. Around 400 BC 'sphairai' were introduced, which were essentially himantes, but they contained a padded interior and the exterior of the thong was more rigid and hard. The Boxer of Quirinal (depicted left) dated to about 300–200 BC shows these straps.

We actually have a very good description about how these boxing matches would have gone: Hómēros in his Iliad describes the boxing match between Epeius and Euryalus:

"Godlike Euryalus alone stood up to fight him, the son of King Mecisteus, Talaus’ son, who at the funeral games for Oedipus, in Thebes, defeated every Cadmeian opponent. Diomedes, the spearman, eager to see him win, helped Euryalus to prepare, and gave him encouragement. He buckled on his belt, and bound the ox-hide thongs carefully on his hands. When the two contestants were ready, they stepped to the centre of the arena, and raising their mighty arms, set to. Each landed heavy blows with their fists, and they ground their teeth, as the sweat poured over their limbs. Euryalus sought an opening, but noble Epeius swung and struck his jaw, and he went straight down, his legs collapsing under him. Like a fish that leaps in the weed-strewn shallows, under a ripple stirred by the North Wind, then falls back into the dark wave, so Euryalus leapt when he was struck, but the big-hearted Epeius, lifted him and set him on his feet, and all his friends crowded round, and supported him from the ring his feet trailing, his head lolling, as he spat out clots of blood. He was still confused when they sat him down in his corner, and had to fetch the cup, his [second] prize, themselves." [Bk XXIII:651]

Riding - Riding--like the chariot races--were for the wealthy. The winners were not the riders themselves, but the owners of the horse. As such, there were actually women who won equestrian events. In the Olympic riding events, held over 6 laps around the track (about 4.5 miles), the jockeys rode bareback. There were separate races for adult horses and foals.

Running - The Olympic Games originally contained one event: the stadion (or "stade") race, a short sprint the length of the stadium. Runners had to pass five stakes that divided the lanes: one stake at the start, another at the finish, and three stakes in between.

The Diaulos (Δίαυλος), or two-stade race, was introduced in 724 BC, during the 14th Olympic games. The race was a single lap of the stadium, approximately 400 metres (1,300 ft), a turn around a post (either an individual one, or a single one) and then the return journey.

A third foot race, the Dolichos (Δόλιχος), was introduced in 720 BC. The length of the race was somewhere between 18–24 laps, or about three miles (5 km). At Olymia, the race started and ended at the stadium, but then wound its way throughout the grounds, passing by important shrines and statues, including the Nike statue by the temple of Zeus. This race was closest to our modern marathon.

The last running event added to the Olympic program was the Hoplitodromos (Ὁπλιτόδρομος), or 'Hoplite race', introduced in 520 BC and traditionally run as the last race of the Olympic Games. The runners would run either a single or double diaulos (see above) in full or partial armour, carrying a shield and additionally equipped either with greaves or a helmet. The armor was a huge hindrance for the otherwise bare runners, as an armor avaraged out between 50 and 60 lb (27 kg). Although many events on the Games were throwbacks to war, the hoplitodromos emulated the speed and stamina needed for warfare. As depicted to the side, runners sometimes dropped their shields because of the weight, and runners would have to jump over it to keep from falling.

From Hómēros, we again have a description:

"Swift Ajax the Lesser, and Odysseus, the cunning, stepped forward, with the fastest of the young men, Antilochus, Nestor’s son. They took their places at the start, and Achilles pointed out the turning post. Off they ran, and Ajax, son of Oïleus, hit the front, with noble Odysseus at his heels, as close as a woman weaving holds the shuttle to her chest, as she draws it along skilfully passing its spool through the warp. He trod in Ajax’s footsteps before the dust had settled, and his breath beat on Ajax’s neck as they ran swiftly on. The Greeks shouted for Odysseus as he strained for victory, urging him on to the utmost. As they were nearing the finish, Odysseus prayed urgently in his heart to bright-eyed Athene: ‘Goddess, hear me, help me if you will and quicken my legs.’ He prayed and Athene heard, making his limbs seem lighter, and just as they reached the line, Pallas Athene made Ajax slip on a patch of offal from the sacrifice of bellowing bulls that fleet-footed Achilles had made in honour of Patroclus. He fell and his mouth and nostrils were filled with offal, while Odysseus came in first, and claimed the silver bowl, leaving the ox for noble Ajax. He stood there, spitting out the offal, grasping the ox’s horn, and complained to the Argives: ‘There, did you see how the goddess made me slip, she who’s always at Odysseus side, helping him!'" [Bk XXIII:740]

Image source: Chariot racing, running, Pygmachia: Wikipedia Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment