The Hellenic pantheon literally has hundreds of Gods, Goddesses, Titans, nature spirits, heroes, kings and queens. Although Hellenismos focusses mostly on the Big Twelve, Hades, Hestia and Hekate, Hellenic mythology is a true treasure trove of immortals. Most of these 'lesser' immortals get very little attention, and I'd like to change this. So, ever now and again, I'm going to introduce one of the lesser known immortals and try and find a place for them in modern Hellenistic worship, based off of their ancient Hellenic worship. Today, I'm introducing to you Hēlios (Ἥλιος), personification of the sun.

Hēlios is a Titan, born from Hyperion and Theia (Hesiod, Pindar), or Hyperion and Euryphaessa (Homeric Hyms). Hyperion (Ὑπερίων), meaning 'The High-One', was born from Gaea and Ouranos. He is the Lord of Light, and Titan to the east. Due to his (and Helios') epithets, there is often confusion between the two: Helios is refered to as 'Hyperion' by Homeros in the Odysseia, and one of the well known epithets of Hyperion is 'Helios Hyperion', yet the ancient Hellens distinguished between Them quite rigidly. Hyperion is the observer--and father--of many of the Titans connected to the sky. Diodoros Sikeliotes (Διόδωρος Σικελιώτης), Hellenic historian and writer of the Bibliotheca historica, says the following about Hyperion:

Theia and Euryphaessa are generally regarded as the same Deathless woman: 'theia' is the Hellenic word for 'Goddess', so it was likely 'Theia Euryphaessa' translated to 'Goddess Euryphaessa'. This means that Hēlios' family tree is as follows:

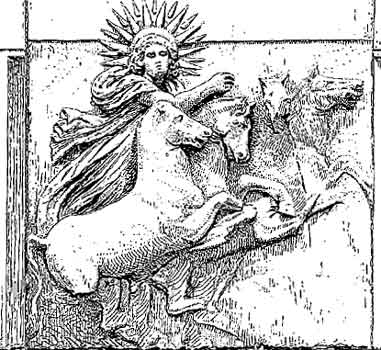

As far as confusion goes, Hēlios is also often confused with Apollon, mostly because of their conglomeration as a single Deity in the Roman era. In ancient Hellas, it was Phoibos (or 'Aiglêtos') Apollon who drove the chariot of the sun through the sky each morning, following the lovely Eos out of the heavenly gates. Phoibos Apollon is associated with carrying sunlight, but He is in no way the sun itself. That honor befalls Hēlios.

Hēlios is the sole Theos described as 'all-seeing' (Panoptes, because His rays reach (almost) everywhere on the Earth's surface. Most famously, He sees Aphrodite' affair with Ares, and warns Hēphaistos of it. As such, Hēlios is regarded as the enforcer of justice and vows. From Orphic Hymn seven:

The most famous piece of mythology concerning Hēlios regards His son Phaethon (Φαέθων), by Klymene (Κλυμένη). The story is told to us by Ovid, a roman poet. In it, Klymene boasts to Phaethon that his father is the sun God Himself, and so, Phaethon goes up to Olympus to confirm. To prove His paternity, Hēlios swears of the river Styx to give Phaëthon anything he desires. Phaëthon grabs this opportunity to demand of his father to let him drive his golden chariot the next time the sun rises.

Hēlios tries to talk His son out of it, claiming that not even Zeus would attempt to drive the chariot, as it is hot with fire and the horses wild and fire breathing. Phaëthon will hear none of it, and so Hēlios must let him get on. He rubs his son's body with magical oil that will protect him from the heat and as Eos and Apollon leave the gates, so does Phaëthon.

The four horses of the chariot--Pyrois, Aeos, Aethon, and Phlegon--sensed Phaëthon's weaker hand and became virtually unsteerable. First, Phaëthon drove them too high, and the Earth below cooled and the people suffered. Then, he flew too low and entire cities burned, lakes and rivers dried up, and even the seas were affected. Mighty Poseidon tried to stop Phaëthon, but had to flee from the heat. It was Zeus who threw His lightning bolt and killed Phaëthon.

Hēlios was inconsolable, and refused to man the solar chariot for days on end. He blamed Zeus for His son's death, but Zeus rightly claimed He had no other choice. The Theoi eventually convinced Him to to take up His responsibility again, but His son's death pained Hēlios greatly. On the epitaph on Phaëthon's tomb was written:

Another piece of Hēlios' mythology comes from Hómēros who writes in the Odysseia:

Yet, not only do they not steer clear of the island, they kill and eat (unbeknownst to Odysseus), some of the sheep in Hēlios' herd as they become stranded on this island for days or even months.

The worship of Hēlios was quite widespread throughout ancient Hellas, but never in a measure beyond a cult. Athenians observed Helios as a Theos, but had no worship for Him. On the island of Rhodes, Hēlios was revered most, although evidence of His worship has been found in Corinth and Hermoine. The Colossus of Rhodes was dedicated to Him and the acropolis of Corinth was part of His worship as well.

For modern practitioners, there is not a lot to go on if you want to honor Hēlios. One can assume that manna is an acceptable offer because of His close identification with Apollon. There is also vague record of a festival on Rhodes, where a chariot with four horses was driven off of a cliff to commemorate the death of Phaëthon, but I would opt against this in modern day society. I would suggest thinking of Hēlios as He rises, and perhaps offering to Him when offering to Apollon in His solar aspects.

Helios is a beautiful, bright and all-encompassing Theos who deserves the worship of modern day practitioners. I, for one, would love to see a new cult rise on His name.

Hēlios is a Titan, born from Hyperion and Theia (Hesiod, Pindar), or Hyperion and Euryphaessa (Homeric Hyms). Hyperion (Ὑπερίων), meaning 'The High-One', was born from Gaea and Ouranos. He is the Lord of Light, and Titan to the east. Due to his (and Helios') epithets, there is often confusion between the two: Helios is refered to as 'Hyperion' by Homeros in the Odysseia, and one of the well known epithets of Hyperion is 'Helios Hyperion', yet the ancient Hellens distinguished between Them quite rigidly. Hyperion is the observer--and father--of many of the Titans connected to the sky. Diodoros Sikeliotes (Διόδωρος Σικελιώτης), Hellenic historian and writer of the Bibliotheca historica, says the following about Hyperion:

"Of Hyperion we are told that he was the first to understand, by diligent attention and observation, the movement of both the sun and the moon and the other stars, and the seasons as well, in that they are caused by these bodies, and to make these facts known to others; and that for this reason he was called the father of these bodies, since he had begotten, so to speak, the speculation about them and their nature."

Theia and Euryphaessa are generally regarded as the same Deathless woman: 'theia' is the Hellenic word for 'Goddess', so it was likely 'Theia Euryphaessa' translated to 'Goddess Euryphaessa'. This means that Hēlios' family tree is as follows:

Chaos --- Gaea

| |

Ouranos --- |

Hyperion --- Euryphaessa

|

Hēlios

As far as confusion goes, Hēlios is also often confused with Apollon, mostly because of their conglomeration as a single Deity in the Roman era. In ancient Hellas, it was Phoibos (or 'Aiglêtos') Apollon who drove the chariot of the sun through the sky each morning, following the lovely Eos out of the heavenly gates. Phoibos Apollon is associated with carrying sunlight, but He is in no way the sun itself. That honor befalls Hēlios.

Hēlios is the sole Theos described as 'all-seeing' (Panoptes, because His rays reach (almost) everywhere on the Earth's surface. Most famously, He sees Aphrodite' affair with Ares, and warns Hēphaistos of it. As such, Hēlios is regarded as the enforcer of justice and vows. From Orphic Hymn seven:

"Dispensing justice, lover of the stream, the world's great despot, and o'er all supreme.

Faithful defender, and the eye of right, of steeds the ruler, and of life the light"

The most famous piece of mythology concerning Hēlios regards His son Phaethon (Φαέθων), by Klymene (Κλυμένη). The story is told to us by Ovid, a roman poet. In it, Klymene boasts to Phaethon that his father is the sun God Himself, and so, Phaethon goes up to Olympus to confirm. To prove His paternity, Hēlios swears of the river Styx to give Phaëthon anything he desires. Phaëthon grabs this opportunity to demand of his father to let him drive his golden chariot the next time the sun rises.

Hēlios tries to talk His son out of it, claiming that not even Zeus would attempt to drive the chariot, as it is hot with fire and the horses wild and fire breathing. Phaëthon will hear none of it, and so Hēlios must let him get on. He rubs his son's body with magical oil that will protect him from the heat and as Eos and Apollon leave the gates, so does Phaëthon.

The four horses of the chariot--Pyrois, Aeos, Aethon, and Phlegon--sensed Phaëthon's weaker hand and became virtually unsteerable. First, Phaëthon drove them too high, and the Earth below cooled and the people suffered. Then, he flew too low and entire cities burned, lakes and rivers dried up, and even the seas were affected. Mighty Poseidon tried to stop Phaëthon, but had to flee from the heat. It was Zeus who threw His lightning bolt and killed Phaëthon.

Hēlios was inconsolable, and refused to man the solar chariot for days on end. He blamed Zeus for His son's death, but Zeus rightly claimed He had no other choice. The Theoi eventually convinced Him to to take up His responsibility again, but His son's death pained Hēlios greatly. On the epitaph on Phaëthon's tomb was written:

"Here Phaëthon lies who in the sun-gods chariot fared.

And though greatly he failed, more greatly he dared."

Another piece of Hēlios' mythology comes from Hómēros who writes in the Odysseia:

"we came swiftly to Helios Hyperion’s lovely island, where the sun-god grazed his fine broad-browed cattle, and his flocks of sturdy sheep. I could hear the lowing of cattle as they were stalled and the bleating of sheep from my black ship while I was still at sea, and the blind seer Theban Teiresias’ words came to mind, with those of Aeaean Circe, who both warned me to avoid the isle of Helios who gives mortals comfort."

Yet, not only do they not steer clear of the island, they kill and eat (unbeknownst to Odysseus), some of the sheep in Hēlios' herd as they become stranded on this island for days or even months.

"Now Lampetia of the trailing robes sped swiftly to Helios Hyperion with the news we had killed his cattle, and deeply angered he complained to the immortals: “Father Zeus and you other gods, immortally blessed, take vengeance on the followers of Odysseus, Laertes’ son. In their insolence, they have killed my cattle: creatures I loved to see when I climbed the starry sky, and when I turned back towards earth again from heaven. If they do not atone for their killing, I will go down to Hades and shine for the dead instead.""

"The gods at once showed my men dark omens. The ox-hides crawled about, raw meat and roast bellowed on the spit, and all around sounded the noise of lowing cattle. Nevertheless my faithful comrades feasted for six days on the pick of Helios’ cattle they had stolen. And when Zeus, Cronos’ son, brought the seventh day on us, the tempest ceased, and we embarked, and, raising the mast and hoisting the white sail, we put out into open water.

"It was not till the island fell astern, and we were out of sight of all but sky and sea, that Zeus anchored a black cloud above our hollow ship, and the waves beneath were dark. She had not run on for long before there came a howling gale, a tempest out of the west, and the first squall snapped both our forestays, so that the mast toppled backwards and the rigging fell into the hold, while the tip of the mast hitting the stern struck the steersman’s skull and crushed the bones. He plunged like a diver from the deck, and his brave spirit fled the bones.

"At that same instant Zeus thundered and hurled his lightning at the ship. Struck by the bolt she shivered from stem to stern, and filled with sulphurous smoke. Falling from the deck, my men floated like sea-gulls in the breakers round the black ship. The gods had robbed them of their homecoming."

The worship of Hēlios was quite widespread throughout ancient Hellas, but never in a measure beyond a cult. Athenians observed Helios as a Theos, but had no worship for Him. On the island of Rhodes, Hēlios was revered most, although evidence of His worship has been found in Corinth and Hermoine. The Colossus of Rhodes was dedicated to Him and the acropolis of Corinth was part of His worship as well.

For modern practitioners, there is not a lot to go on if you want to honor Hēlios. One can assume that manna is an acceptable offer because of His close identification with Apollon. There is also vague record of a festival on Rhodes, where a chariot with four horses was driven off of a cliff to commemorate the death of Phaëthon, but I would opt against this in modern day society. I would suggest thinking of Hēlios as He rises, and perhaps offering to Him when offering to Apollon in His solar aspects.

Helios is a beautiful, bright and all-encompassing Theos who deserves the worship of modern day practitioners. I, for one, would love to see a new cult rise on His name.

-

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

ancient Hellenic culture Apollon Eos Euryphaessa Gaea genealogy Hēlios Hellenismos 101 Hesiod Hómēros Hyperion Introduction series Klymene Mythology 101 Odysseia Ouranos Ovid Phaëthon Styx

5 comments:

I tend to give worship to Helios when I do my morning and evening rituals to Apollon. I don't maintain an altar for him distinctly but rather have been setting up a small corner of Apollon's altar for him and I have been working on some designs for a small image of Helios to be set there for his associations with Apollon. I think of Helios in terms in which Plato describes the hosts of the gods, and that each Olympian had within his host a number of gods which are aligned to his domain (my paraphrase). Thus Helios is linked to Apollon but is of course an entirely separate divine being. I have always said for folks to reduce Apollon into the same identity of Helios is a disservice to both gods, but to honor them together is another thing.

In any case most of my prayers to Helios are done outside with gaze directed to the rising, or setting sun, something which gets harder to do in the winter here in Alaska with how late the sun rises and how early it sets lol. Helios just barely skims above the horizon :)

I think your methods would work very well for many Hellenists. Plato's thoughts on this are interesting, indeed, and there is a lot of truth to them. Like I said, the two are interlinked, but hardly the same. Worshipping Them together makes sense, though. They travel together as well.

Worshipping Apollo and/or Helios in Alaska sounds like a challenge, indeed! Good luck during the dark months, and be careful not to miss your tiny window of opportunity ;)

Thank you for your comment!

thanks for this awesoem info, i always have worshipped Apollo as being teh all seeing etc, but I am now coming to terms with Helios being separate from Apollo

Apollo is definitely a solar Deity, but Helios has dibs ;) I'm glad you got something out of this post. Thank you for your comment!

From Theoi.com: "Theia" means "Sight" or "Prophecy":

http://www.theoi.com/Titan/TitanisTheia.html

"Goddess" is "thea", similar but without the "i".

I don't want the trouble of trying Greek letters here, but find in original and check Theogony 135 for Theia vs. Iliad 1:1 for Thea.

Post a Comment