Two-and-a-half millennia ago, Athenian artist Phidias depicted the Hellenic myth of the Centauromachy in his sculptures for Athens’ Parthenon. Athens, the wealthy and powerful democratic nation-state, was of course analogous in the story to the civilized Lapiths; any foes the city faced resembled the barbaric Centaurs, who, as the tale goes, attempted to rape the bride at a Lapith wedding feast, launching a battle between the two peoples. The Parthenon still stands all these centuries later, but Phidias’ work, which once adorned the building, is scattered between the Athens’ Acropolis Museum and the British Museum nearly 2,000 miles away.

It’s been more than 200 years since Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin, obtained a royal Ottoman mandate to excavate near the Parthenon, document the sculptures, and “take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions, or sculptures therein.” An international debate has raged ever since: Did Britain’s Lord Elgin, who was the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which then ruled Greece, have the legal right to remove the sculptures? Should the British Museum, the current home of the sculptures, yield to Greek demands for their return?

Recently, a line in a potential post-Brexit trade deal being drafted by Europe demanding that Britain “return unlawfully removed cultural objects to their countries of origin” has reignited the debate. It’s an issue that, much like Brexit itself, boils down to a question of “Leave” or “Remain.” But perhaps it’s also a question of who, in modern Europe, are the civilized Lapiths, and who are the barbaric Centaurs?

To understand the turns the discussion has taken, it’s helpful to go back to the sculptures’ beginning, 2,500 years ago, when the Athens city-state was at the height of its power and influence—Euripides and Sophocles were writing their great tragedies; Socrates was still young.

After a Persian invasion destroyed an older temple, Athens celebrated Greece’s victory by building the Parthenon in its place. Its name means “the virgin’s abode,” and the temple was dedicated to Athena, the virgin goddess of war and wisdom. Though a temple, it was not strictly a religious site and was used as a treasury.

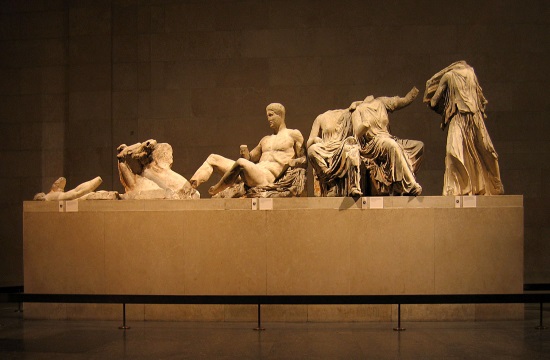

The building featured hundreds of sculptures by Phidias, one of the greatest artists of Ancient Greece, whose figures tell stories of gods, celebrations, and battles. Phidias installed finely carved sculptures on multiple levels of the building: the most fully modeled were on its pediment, while the 92 highly sculpted friezes known as the metopes, sat right below the roof. Finally, the frieze, in low relief, lined the walls just above the temple’s inner columns.

Like the Centauromachy, some of the stories carved into the marble are allegorical. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that the frieze contained exactly 192 horsemen, which was the number of Athenian warriors who died at the Battle of Marathon during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

The beauty and detail of the sculptures are truly awe-inspiring—every fold of every peplos, the draping, sleeveless tunic favored by women of ancient Greece, is included; not even fingernails are neglected on a frieze that was mounted 30 feet above eye level. At the center of the temple stood a giant gold-plated statue of Athena herself, known as the Athena Parthenos. At some point, that sculpture disappeared from the temple and the historical record, its whereabouts unknown.

Over the millennia, the Parthenon has changed with times, states, and faiths. Around 450 A.D., it was rededicated to a different virgin saint, Mary of Nazareth, and next became a mosque after the Ottomans took Athens in the 15th century. When a Venetian shell hit the temple in 1687, during a war between the Turks and Venice, it became the temple we know now—a ruin.

That was how Elgin viewed it at the dawn of the 19th century, when, armed with his mandate from the royal Ottoman empire, he chiseled off and conveyed to England the sculptures, metopes, and friezes from the temple that would become known as the Parthenon Marbles.

It has since been the subject of fierce debate whether or not the hazy perimeters of the stunningly inexact document Elgin obtained allowed him to simply sift through the debris surrounding the Parthenon and collect any treasures that had already fallen from the building, or remove the works from the structure.

By contemporary standards, what happened at the Parthenon was deeply unethical. No major institution like the British Museum would today acquire artifacts from an occupied land under the permission of the invading force. But those who would return the sculptures see the question of lawfulness simply: “They were ‘stolen’ in that an alien Ottoman regime was in power at the time,” says Dame Janet Suzman, celebrated Shakespearean actress and chairperson of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

And this isn’t merely a modern interpretation of Elgin’s actions: Even in 1801 contemporary witnesses to the despoiling of the Acropolis were framing the situation as a tragedy. “Athena wept over her lost virginity,” one traveler wrote at the time.

In 1816, the British Museum bought the Marbles from Elgin. The Elgin Marbles, as they became known, became an instant phenomenon when they went on view the following year. Keats was observed gazing at them in an uninterruptible rapture, and wrote his famous sonnet “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” in response. The French Romantic Alphonse de Lamartine declared the Marbles “the most perfect poem ever written in stone on the surface of the earth.”

But they were also instantly controversial when they went on view—even in early 19th-century England, it was considered shocking for an ancient monument to be stripped of its adornments. Byron, Greece’s most famous foreign champion, was appalled, and dedicated five stanzas of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” to his outrage.

The British Museum, would, in turn, begin to justify its possession of the marbles by positioning itself as preservers of the sculptures, which the Ottomans had taken to grinding up for limestone. More recently, the institution has gone on to argue that it sheltered and preserved the marbles from environmental damage as the Parthenon was subject to acid rain and other environmental pollutants.

But those who advocate for repatriation point to the shoddy record of British care for the marbles, starting with the two years some of the works spent at the bottom of the ocean when one of Elgin’s ships sank, and continuing through a 1930s effort to scrub them whiter-than-white with steel wool and household bleach. In 2014, Britain undermined its longstanding argument that the Marbles were too fragile to be moved by loaning them to a museum in St. Petersburg.

The controversy will not go away, especially at the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery, which attempts to help visitors envision the works as they were intended to be displayed. Here, it’s impossible to escape the fact that this is not the way these works were supposed to be displayed. The sculptures of the east pediment are arranged at one end of the rectangular gallery; the sculptures of the west at the other, while friezes and metopes line the walls in between at eye level. This attempt to emulate what was lost in stripping the stones from the Parthenon only underscores one of the most convincing arguments cited by those who would repatriate the Marbles to Athens: this art is intensely site-specific.

“This case is unique because the Parthenon itself is standing there,” says political sociologist and University of Virginia researcher Fiona Rose-Greenland. “So you have the idea that these things are actually ornaments for a structure that exists. It’s not like they were statues pulled out of the ash heap of some building that’s no longer there.”

The Duveen Gallery does contribute one major benefit to viewers—they’re no longer dozens of feet from the ground, as they were when they decorated the Parthenon. But Phidias explicitly carved the sculptures with this distance in mind; figures in the frieze were sculpted to account for the distorting perspective of eyes 35 feet below.

Though no one will ever again stand at the Parthenon and gaze up at the sculptures above, it would be possible for visitors to see the art closer to its birthplace. Partially in response to the British Museum’s long-held contention that Greece lacked a suitable home for the Marbles, the country in 2003 opened the Acropolis Museum, where the Parthenon sculptures owned by Greece are now displayed. The Parthenon itself is visible from the galleries of the Acropolis Museum, “an eye flicker [away] from the picture window in the dedicated Parthenon Gallery,” according to Suzman.

Though a British government spokesperson recently said that returning the marbles is “not up for discussion as part” of the Brexit trade deal, there are precedents for similar returns of ancient art. In 2006, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art agreed to repatriate to Italy the Euphronios Krater, a terra cotta bowl that predates the Parthenon by approximately 100 years. The Krater may be the finest surviving example of ancient Greek pottery, and in 1972 the Met purchased it for more than one million dollars, a staggering amount at the time. But the bowl had been looted from an Italian tomb, and eventually the museum agreed to return it to Italy, in exchange for three lesser early vases.

Opponents of repatriation in the op-ed pages of the British press trot out the rather hoary argument that the return of the Marbles could lead to the gradual emptying of the world’s encyclopedic museums. The Rosetta Stone would follow the marbles out the doors of the British Museum shortly thereafter, then Berlin’s Neues Museum would be forced to ship its bust of Nefertiti back to Egypt. In fact, Egyptian wings the world over would be empty husks.

It is in global institutions like the British Museum, these advocates argue, that art achieves its true cosmopolitan promise. If art is for all peoples and all ages, then it’s most appropriate that it be showcased in museums featuring art made by all peoples during all ages, rather than segregated in far-flung state museums that serve narratives of glorious nationalistic pasts. Shortly after the Euphronios Krater was returned to Italy, a reporter for the New York Times noted that the bowl didn’t seem to attract many visitors in its new-old home. Is the Krater better served at the relatively little-known Cerveteri Museum where it now resides than it was at the Met, with its more than 6 million annual visitors?

But, “if really what we’re talking about is equal share for all, and a universal culture, then why isn’t there an old Dutch masters museum in Namibia?” asks Rose-Greenland, “Why isn’t the Art Institute of Chicago handing over its exquisite collection of French 19th-century watercolors to a Peruvian museum for a long-term loan?”

“Ownership necessarily betrays historical balances of power,” says James Cuno, art curator, historian, and president and CEO of the Getty Trust. But he argues that the fact that Western developed nations possess a disproportionate share of the world’s encyclopedic museums doesn’t mean that the idea of such museums is invalid. The cure isn’t fewer encyclopedic museums, but more of them, in more countries.

More problematic is another question raised by some supporters of global museums—that contemporary communities lack serious claims on objects built for and by people who lived centuries ago on the same patch of earth. The logic of this objection is that either art knows no age or national boundary, or it so grounded in its context that every other culture and era is equally without claim to it.

In his book Cosmpolitanism, Kwame Anthony Appiah argues that parsing thousands of years of human creation into categories of “yours” and “mine” isn’t easy, particularly since it can hardly be argued that the ancients were creating art with any of us in mind. He points out that the Euphronios Krater, found in and returned to Italy, was actually a Greek bowl. “Patrimony, here,” he writes, “equals imperialism plus time.”

In the case of the Parthenon Marbles, however, the suggestion that contemporary Greek people are not the legitimate heirs of Ancient Greece has a very ugly history. Elgin himself remarked that “The Greeks of today do not deserve such wonderful works of antiquity,” and “[Modern Greeks] have nothing whatsoever in common with [Ancient Greeks]. He made this claim based on the idea, popularized by the 19th-century Austrian travel writer and theorist Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, that modern Greeks are descended from Slavs. “The race of the Hellenes has been wiped out in Europe,” he wrote in 1830. “Physical beauty, intellectual brilliance, innate harmony and simplicity, art, competition, city, village, the splendour of column and temple … [have] disappeared from the surface of the Greek continent.”

Though controversial from its inception and now debunked, Fallmerayer’s implicitly racist theory has appeared as recently as 2015 in the conservative German newspaper Die Welt, in an article in which the author argued that Greece was the perpetual demolisher of Eurozone order, from the early 19th century through austerity. He writes that Greeks are not “descendants of a Pericles or Socrates” but “a mixture of Slavs, Byzantines, and Albanians”—less worthy of a place in the European order, pretenders to admission to the EU. As if foretold in Phideas’s sculptures of the Centauromachy, the discussion has been reduced to an explicitly racist rumination on who inherits the title of civilization from the Ancient Greeks, and who is cast out as a barbarian.

The works of Phidias were completed in 432 B.C., but it might be argued that the Parthenon Marbles were created in 1687 when that shell turned the Parthenon into a husk and many of its adornments to dust. These were the sculptures that Elgin began excavating in 1801— and no one can argue that the 19th-century Greeks who watched the Parthenon defiled are unrelated to the Greeks today who clamor for their return.

The Parthenon Marbles as they are now are not the same art as the works Phidias painted and sculpted. Recreations of the works are almost jarring—their bright colors seem garish to contemporary eyes—accustomed as we are to the cool white scrubbed marble that western curators claimed showed the elegant simplicity of Ancient Greece. And of course, in the place of missing faces and limbs we project our own imaginings of the ancients, projections that have become part of the works themselves. As Margaretha Rossholm Lagerlof writes in The Sculptures of the Parthenon, “The ancient artifact naturally possesses a certain sublimity from the sheer passing of time, but also because it represents an unfilled and unfillable void.”

Source and more images here.

:focal(396x228:397x229)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/46/3d/463d428e-22b2-499b-8a40-3e4024785719/cupid.jpg)